Kellie Castle lies beyond the fishing village of Pittenweem in Scotland. Originally built in the twelfth century, it was leased to the prestigious Lorimer family in 1878. The Lorimers have been compared to a Renaissance dynasty; James Lorimer (1818-1890), was an eminent professor of law and his sons were the renowned architect Sir Robert Lorimer (1864-1929) and John Henry Lorimer (1856-1936), the painter. A lesser known part of the Lorimer legacy was their sister, Hannah (1854-1947). A gifted artist and craftsperson in many media, Hannah is more commonly remembered for her marriage to Sir Everard im Thurn, the governor of Fiji. Although Hannah was never considered a professional artist, she created an impressive body of work now held by institutions including the British Museum, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, the Pitt Rivers Museum and also the Guyana National Museum.

Hannah was raised in Edinburgh and earned a Certificate in Art for Women in Moral Philosophy and Geology from the University of Edinburgh in 1880. Women were not permitted to graduate with degrees from the university until 1894. Hannah practiced painting with her brother John Henry, and copied several masterpieces including Botticelli’s The Madonna of the Magnificat and Henry Raeburn’s portrait of Thomas Reid. Hannah’s copy of the latter hangs in the Library at Kellie Castle.

Copying paintings was a way for Hannah to refine her skills, as traditional art tuition was not as widely available or appropriate for women. Regardless of this, Hannah exhibited artwork at the Royal Scottish Academy with John Henry.

In her early twenties, Hannah’s father James took up the tenancy at Kellie Castle. From Kellie, Hannah taught art by running a postal art course throughout Europe. A lifelong learner, Hannah was also determined to assist in renovation work at Kellie Castle. She learned to mould plaster ceilings at Kellie from her brother Robert and there is evidence that she also completed the plaster ceilings at Falkland Palace during its extensive renovation. Hannah also used her skills in plaster for sculpture.

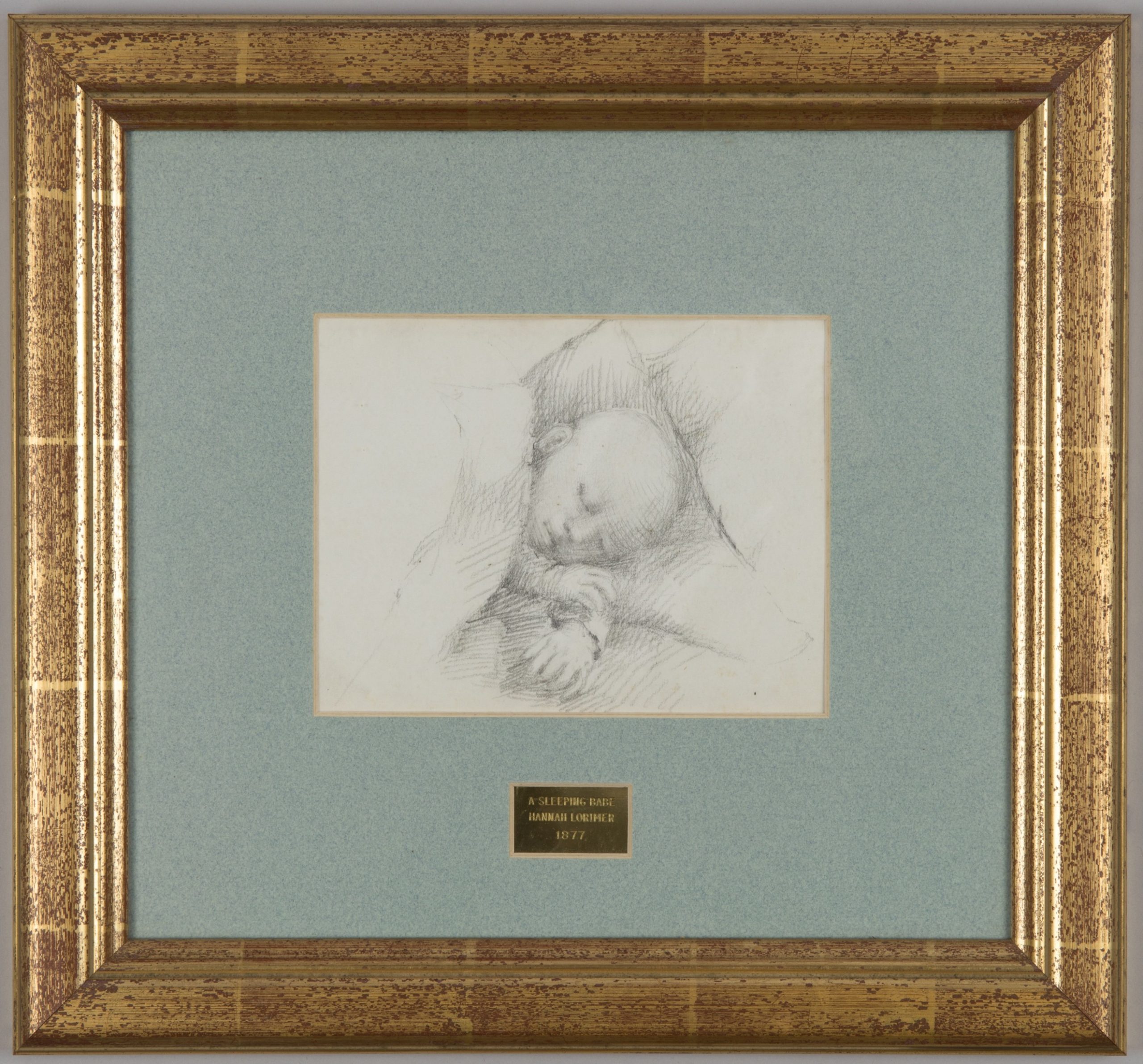

Much of Hannah’s artwork from this time features the theme of childhood and motherhood. Although she never had children of her own, she was beloved by her nieces and nephews.

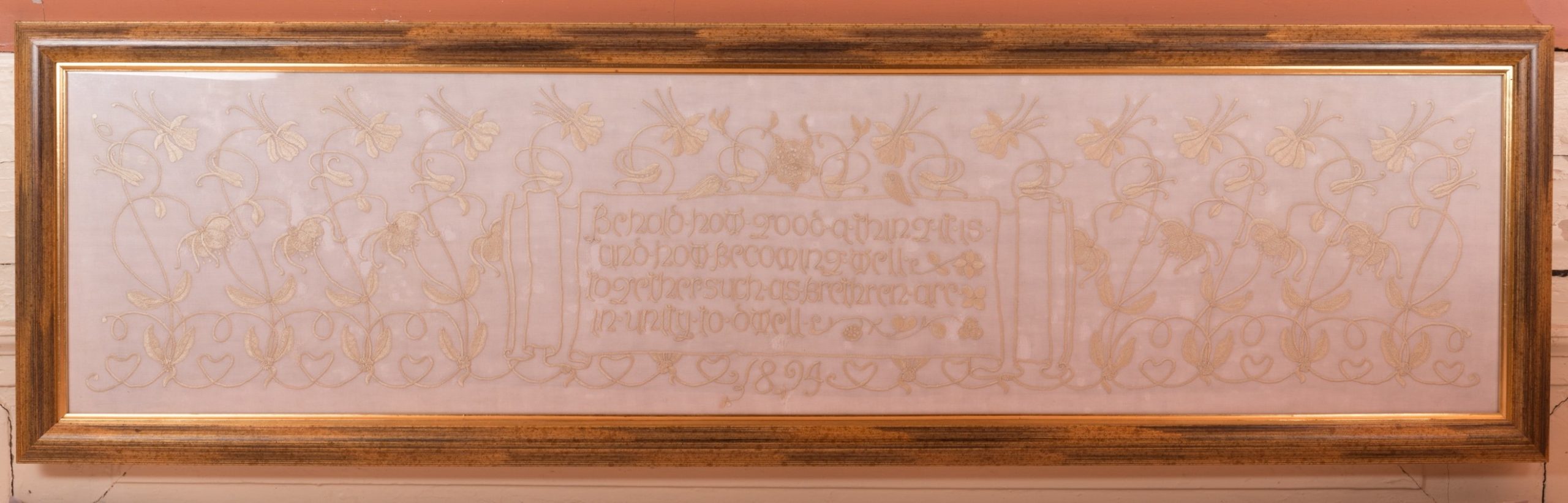

Hannah was also talented in music and needlework. This panel at Kellie Castle demonstrates her mastery, as white thread on white ground requires a skilled hand.

When Hannah married Everard in 1895, they embarked on international travels that inspired her art. Everard was a botanist and photographer as well as a colonial administrator. His expedition to Roraima Plateau is said to have inspired Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912). On their travels Hannah assisted Everard by painting watercolours of orchid species that he studied. These watercolours are now in the collections at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. She also sculpted plaster busts of local boys in some of the places they travelled, including Sri Lanka.

While Hannah was abroad, another talented female artist graced the halls of Kellie Castle. A letter to Hannah from Robert detailed an upcoming visit by Phoebe Anna Traquair, who would paint a panel in the Drawing Room. The letter even included a small sketch of the panel. The Lorimers hosted Traquair in the summer of 1897 and during this time she completed Cupid’s Darts, a colourful scene of five maidens following Cupid through local Scottish woods. In the 1940’s the painting was covered with cartridge paper and flour paste as it was considered gaudy by the inhabitants of the castle. It was forgotten until 1996, when conservation efforts recovered the painting with minimal damage.

A vast majority of Hannah’s work remains at Kellie Castle. Recently, Hannah’s story has received more attention and the National Trust for Scotland has made efforts to showcase her talents. In March 2019 the Curator for Edinburgh and the East, Antonia Laurence-Allen, completed a redisplay in parts of the castle to feature Hannah’s work. She says “It was important to display the sketches and plaster casts by Hannah because her work had been in store for many years, yet she was as skilled an artist as her brother John Henry Lorimer. Her work is sensitive and bold, revolving around childhood and nature; I believe she was inspired by life in the summer sun at Kellie Castle.”

Although Kellie Castle is not open to the public now, below are some resources from the National Trust for Scotland to learn more.

References

- https://www.nts.org.uk/stories/the-lost-lorimer-rediscovering-the-extraordinary-life-of-hannah-lorimer-kellie-castle

- https://www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/kellie-castle