It was natural for women to play a crucial part in the development of textiles. During the Victorian period sewing and embroidery had been an acceptable homemade art worked quietly in private. The Arts and Crafts period however increased both the potential and public visibility of such crafts. Under the art school direction of enlightened educators such as William Lethaby, Walter Crane and Francis Newbery, women were given the chance to study and enter the world of professional design and making. British art schools which led the way included those in Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and, in London, arguably the most influential of all, the Central School of Arts and Crafts founded in 1896.

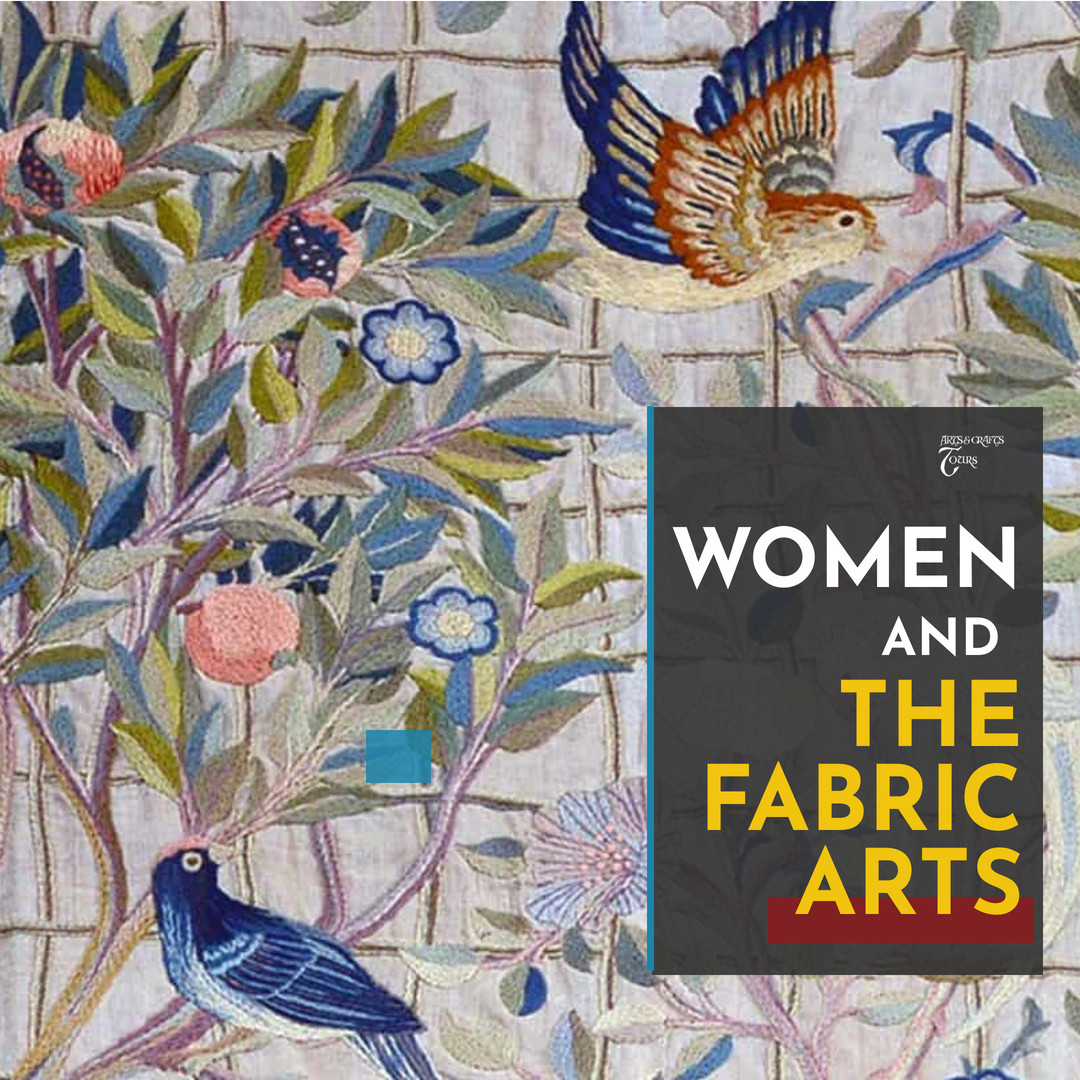

Two influential textile artist-teachers were May Morris (1862-1938), the younger daughter of William and Jane Morris, and Jessie Newbery (1864-1948). Morris managed and designed for the embroidery department of her father’s firm, taught the subject at the Central School and in Birmingham, and wrote articles and books including Decorative Needlework (1893). Her embroidery style is finely detailed and evolved the lyrical naturalism of her father’s design. Newbery, married to ‘Fra’ Newbery, director of the Glasgow School of Art, headed its embroidery department where she encouraged simplicity in design and the use of inexpensive materials. Using simple linens and calicos, appliqué work using silks and beads – a material shared with May Morris – could be used sparely to maximum effect. Her approach was in contrast to that of Edinburgh’s Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852-1936) who completely covered her linens to realise pictorial images of romance drawn from literature and her imagination. All used traditional stitches such as stem stitch and couching but in highly imaginative ways which explored the power and richness of materials and colour.

In the 1880s embroidery was used on furniture from bed hangings and coverlets to draughtscreens and the ever popular portières (door curtains). Along with the advancement of art school courses in the 1890s it became a feature of the simple artistic dress movement. As fashionable interiors became less cluttered towards the 1900s so the role of textiles, including embroideries, was refocused. They were given more space, framed to occupying plainer walls. Overmantels, bedheads, embroidered lampshades and wall panels featured in artistic homes. Crucial to the growing taste for such work were the public art exhibitions, notably those of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. Before the war books appeared to offer guidance on making simple house furnishings and clothes for women and girls. A particularly influential one was Educational Needlecraft (1911), written by Newbery’s successor, Ann Macbeth (1875-1948) with children’s teacher Margaret Swanson.

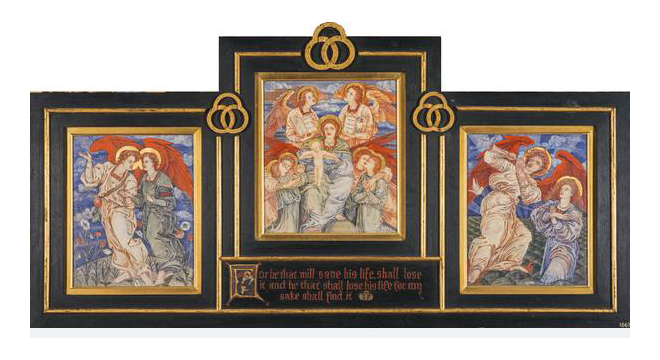

For a decade either side of 1900 churches were widely embellished with both Arts and Crafts embroideries and stained glass, bringing colour and beauty to their interiors. In retirement in the Lake District, Ann Macbeth stitched altar frontals for her local community which brought together religious and landscape images. At the time, appliqué embroidery was likened to stained glass with its outlines compared to lead lines. In Birmingham Mary Newill (1860-1947), teacher at the art school, was one who designed both domestic leaded windows and linen wall hangings.

Mottos celebrating hearth and home, a popular Arts and Crafts feature across a range of materials, were often used for domestic panels. They were popular across the country but most often used by Jessie Marion King (1875-1949) and other ‘Glasgow girls’. It is not surprising therefore that women proudly made banners in support of the women’s suffrage movement, and these, like church work, were made for public display. Ann Macbeth was one who thus sewed her political will into her craft.

The other side of the story is the production of printed textiles. Although few women were employed before the war as commercial designers as opposed to factory hands, enlightened firms such as Alexander Morton did recruit art school-trained women such as Macbeth. The next generation set up their own printed textile workshops, of which the best known was that of Phyllis Barron (1890-1964) and her partner Dorothy Larcher (1884-1952). Working together in Hampstead, London, in the 1920s they moved to the Gloucestershire village of Painswick in the 1930s, where they produced textiles which used their home-grown plants for dyes and inspiration. Barron’s geometric designs for furnishing fabrics were less organic than those of Larcher. One of their pupils was Enid Marx (1902-98) who became known for her industrial textile designs for London Passenger Transport but was also a book artist and a distinguished wood engraver. In her work, as that of many women over the previous half century, art and craft production were closely related.

Bibliography

- Jude Burkhauser (ed.), The Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design 1880-1920, Edinburgh, 1990

- Annette Carruthers and Mary Greensted, Simplicity or Splendour, Arts and Crafts Living: Objects from the Cheltenham Collection, Cheltenham, 1999

- lan Crawford, By Hammer and Hand: the Arts and Crafts Movement in Birmingham, Birmingham, 1984

- Elizabeth Cumming and Wendy Kaplan, The Arts and Crafts Movement, London and New York, 1991

- Elizabeth Cumming, Phoebe Anna Traquair 1852-1936, Edinburgh, 2005

- Elizabeth Cumming, Hand Heart and Soul: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland, Edinburgh, 2006

- Wendy Kaplan, The Arts & Crafts Movement in Europe & America, London and New York, 2005

- Karen Livingstone (ed.), International Arts and Crafts, London, 2005

- Linda Parry, Textiles of the Arts and Crafts Movement, London and New York, 1988