During our research for The Arts and Crafts Movement in the Pacific Northwest (Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, 2007) Glenn Mason and I sought to discover some of the progressive British and Continental connections that inspired architects and designers in Washington and Oregon at the turn of the 20th century. We knew that leading design journals, such as The Studio, were available in the public libraries in Portland and Seattle, that architects subscribed to British, French, and German periodicals and plan books that informed them, and that academic study abroad and travel to world’s fairs broadened their exposure to the latest thinking on buildings and interiors. But there were more direct connections as well. I owe a debt of gratitude to Ashbee scholar James Elliott Benjamin, whom I invited to Seattle in 2003 to present a lecture at Historic Seattle, “Through English Eyes: C.R. Ashbee and the American Arts & Crafts Movement.” He shared a discovery he had made in his research.

During his January 1909 lecture tour to the West Coast, the renowned British designer C. R. Ashbee presented three lectures on the Arts and Crafts in Seattle and one in Portland, Oregon. Ashbee’s critiques when he was touring the US are most revealing. He was quite blunt in his opinions about what he saw on his trip. He despised the work at the Gorham silver factory and called Rookwood’s pottery “rubbish.” Unimpressed by what he referred to as the crowding, pollution, and degradation he had seen in New York, Pittsburgh, and Chicago, he was fascinated and delighted with the West. Ashbee wrote in his journals that Seattle was “the only American city I have so far seen in which I would care to live. All the gold of Ophir would not tempt me to live in one of those smug eastern cities… Here is a city with a new light in her eyes.” While there, he described the city’s landscape and people and visited the studio of the photographer Edward Curtis.

His wife, Janet, remarked on the city’s cosmopolitanism, its “well-appointed restaurants decorated with the latest Arts and Crafts distinction of line and coloring.” While searching downtown restaurants in today’s Seattle will not yield any that Mrs. Ashbee would have visited—nor those that evoke the ambiance she noted—her comments reveal that the Pacific Northwest was participating actively in the important design and reform movement that had roots in nineteenth century Britain but soon was taken to heart by America.

The ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement found fertile ground in Washington and Oregon. The effect was seen in a remarkable variety of public and private architecture and the establishment of Arts and Crafts societies and guilds that trained art workers and hobbyists alike. Many regional architects and designers were inspired by the English. Architect Wade Hampton Pipes, for example, studied at London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts during its golden age as a teaching facility for art workers before opening his Portland, Oregon practice in 1911. He built a reputation on his English Arts and Crafts residences.

Elbert Hubbard’s Roycroft community in East Aurora, New York, had begun largely as a printing press and bindery, inspired by the work of William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, which closed in 1897 but which C.R. Ashbee continued with many of the same printers and craftspeople in his Essex Press. Janet Ashbee had visited Roycroft in 1900 while her husband was lecturing in nearby Buffalo and shared her positive and negative impressions with CRA. It may have fed into his decision a year later to move the Guild from east London to Chipping Campden where Hubbard was entertained. These pivotal experiences could have led to his expansion of product lines in his workshops and nationwide marketing and sales.

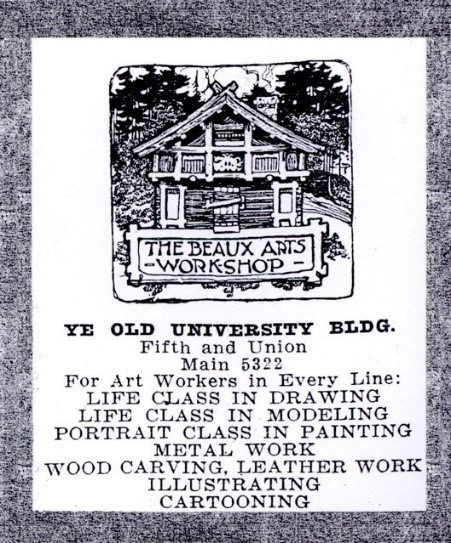

The prolific promoter traveled throughout America, including Spokane, Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, Salem, and Eugene, on lecture circuits. Frank Calvert and Alfred Renfro the founders of Seattle’s Beaux Arts Society and Workshops in 1908, planned a 50-acre community where art workers could “live together, work together and play together,” on the shores of Lake Washington inspired by Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft and Hubbard’s Roycroft.

Years after our book was published and a subsequent exhibit had toured museums in Washington State, I happened to be discussing Arts and Crafts with an architect at a holiday party when a woman who had been listening came up to me and shared that she was the grand-daughter of Alec Miller, who apprenticed at Ashbee’s Chipping Campden workshop in 1902 and stayed with the Guild until its closure in 1907. In his later years, Miller had written a memoir of his time there. She offered to share the unpublished manuscript with me, and it provides a wonderful, personal perspective on the operation of the Guild, the daily routines, the professional and paternal relationship that Ashbee had with his workers, the remarkable gathering of artists, musicians, and writers who regularly paid visits, and the varied skill sets that Miller learned along the way in wood carving and sculpture that would determine his future pursuits.

He wrote, “The history of the Guild if it is to be recorded must be told as of an experiment, not only in the field of arts and crafts, but as an experiment in living also. The Guild and its founder never confused living with making a living! Perhaps that was its undoing, It was for twenty years a living organism, and the life-blood which vitalized the body through all the veins and arteries was the enthusiasm, the persistence, the creative energy and the wide sympathetic affection of its founder.”

In addition to Ashbee’s influence, Pacific Northwest architects and craftspeople benefited from knowledge about the work of British, Scottish, German, and Austrian designers, and I have included illustrations of a few of these projects.