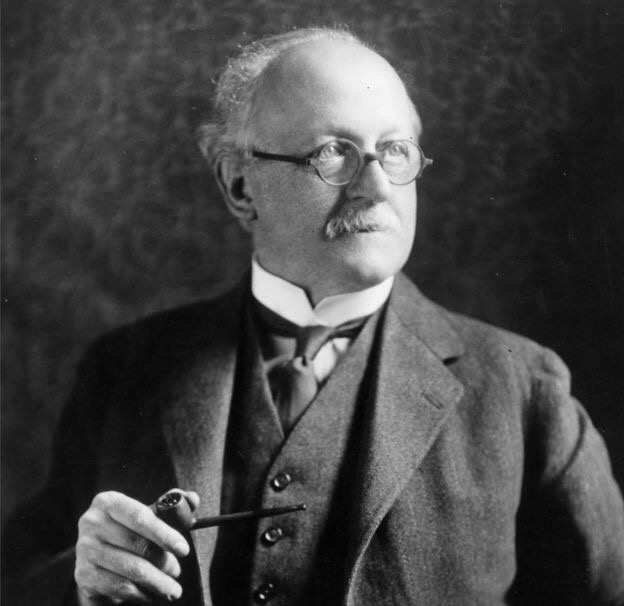

As the London Times noted recently: ‘March 29, 2019 is etched in the minds of many. No, not as the date that was set for Britain to leave the EU, but the 150th anniversary of the birth of Sir Edwin Lutyens.‘ The young ‘Ned’ Lutyens’s father was a painter of horses and had him christened Edwin Landseer in honour of his hero, the artist Sir Edwin Landseer, beloved by Queen Victoria and later to be celebrated throughout the world as the painter of The Monarch of the Glen.

Ned Lutyens was precocious and a compulsive drawer. He set up his own architectural practice in 1888 at the age of nineteen, having already completed his studies at the South Kensington Schools and worked briefly for the practice of Ernest George and Peto. His first commission was a house in Surrey, at which time he met the renowned landscape gardener Gertrude Jeckyll, initiating a partnership that was to have an effect world-wide in regard to the relationship between building and nature, and we will see tangible proofs of this when we visit Le Bois des Mouitiers (1898) at Varengeville in June. A few years later he built Munstead Wood for Miss Jeckyll, a landmark in domestic architecture, and in 1904 the German writer and architectural critic, Hermann Muthesius, in his great work, Das Englische Haus, predicted that Lutyens, who was still only thirty five, would ‘soon become the accepted leader among English builders of houses.‘ He was not wrong!

Lutyens was the most inventive British architect since Sir Christopher Wren, as is borne out by the seldom seen La Maison des Communes, built on a triple-butterfly plan, which we will visit while we are in Varengeville. However, he was not just content to design and build houses. The imperial city of New Delhi, which he planned and created in an often uneasy partnership with Herbert Baker, is architecture on the grandest scale, and the gardens of the Viceregal (now the Presidential) Palace are yet another tribute to his collaboration with Miss Jeckyll. However his greatest work was still to come.

Towards the end of the war he was appointed one of the three principal architects to the Imperial War Graves Commission. Among the many monuments and memorials he was to design is the Monument to the Missing at Thiepval, which we will also visit in June. This stark monument is not only awe-inspiring in its complexity, it is also chilling in the respect it inspires for those tens-of-thousands of British and Commonwealth soldiers, whose bodies were never found but whose names are here engraved in stone – ‘Their Name Liveth For Ever More’. This great monument , with its elaborate geometry, stands in stark contrast to his simplest – and possibly best known – memorial, the Cenotaph in London’s Whitehall, the scene of the annual Service of Remembrance.

Join us in June in Normandy and Picardy when we can toast his memory once again, perhaps this time with a glass of the refreshing local cider, or even calvados.