Northumberland forms the northernmost region of England. Remote and sparsely populated, even today the very name of Northumberland conjures images of wild hills, untamed moorlands and craggy windswept coastline. Its history is swathed in the mists of time, being intertwined with that of the ancient kingdom of Northumbria, the Irish missionary monks of Lindisfarne, and the skirmishes of the borderlands that took place here between Scotland and England.

One of the fiercest and most famous of these battles was the Battle of Flodden Field, immortalised by Sir Walter Scott in his poem ‘Marmion’. Against such a background, it seems strange to report that within eye shot of Flodden Field, lies an exquisite and immaculately preserved testimony to high Victorian culture and the arts. In this bare and distant location, in the second half of the nineteenth century, a miniature hub of art and sophistication arose.

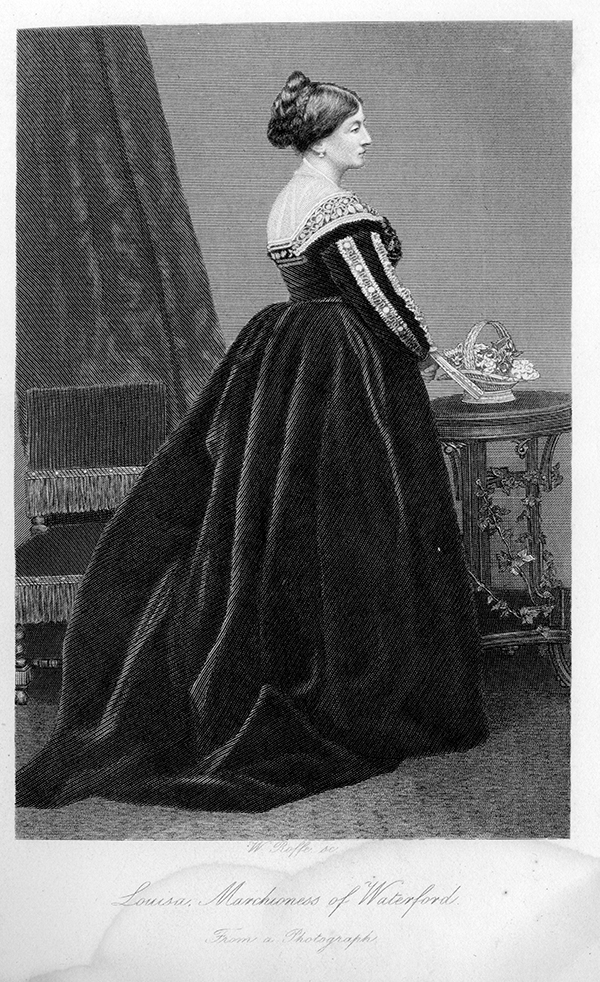

The place described is Ford, which is both a village and the site of Ford Castle and its estate. It was here that Louisa, Marchioness of Waterford made her home for thirty-seven years. At a time of deep emotional desolation in her own life, she came to this desolate landscape, notwithstanding, she went on to fill her home and surrounding estate lands with life, beneficence, and beauty.

The story of Louisa Waterford’s life is perhaps no less filled with contrast than the place that she created in the setting where it is to be found. Her life began in the British Embassy at Paris during the politically precarious aftermath of the Napoleonic wars. Her father, Charles Stuart, who had been aide de camp to the Duke of Wellington during his historic military campaign in continental Europe, was appointed to the role of British Ambassador to France at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Upon assuming his new role, Stuart sought an ambassadress. With cool acumen his choice fell upon Elizabeth Yorke, third daughter of the Earl of Hardwicke, who, although of plain appearance, was fluent in French, had impeccable etiquette, and was universally and unerringly charming. The couple, who were always spoken of as the ‘best of friends’, presided over some dazzlingly successful years at the Embassy.

During their early years at the Embassy, the couple had two children. Charlotte, born in 1817, and Louisa, born in 1818. Louisa was a lively happy child, blessed with doting parents, who adored both her and her elder sister. Life at the Embassy was vivacious and prestigious. The family lived between Paris, Dorset and London. From an early age, Louisa’s talents as a singer and an artist began to manifest. Her ethereal aura of being slightly apart from the world was already present.

Sharp society tongues had long dubbed Charles and Elizabeth ‘the ugliest couple in Europe’. Despite this their daughters grew up to become two of the most celebrated beauties of London society. Charlotte early became the wife of Charles, Viscount Canning, who would later become the first Viceroy of India. Louisa had many suitors, although it seems that for a long time her subtle spirituelle nature remained unmoved by romantic affection. She travelled with her parents to Italy, informally studying art. Upon return, her time was spent between the family’s fashionable residence at Carlton House Terrace, overlooking the Mall in London, and Highcliffe Castle on the Dorset coast, a fanciful Gothic revival country retreat devised by her father. Already in London, Louisa was esteemed for her Raphaelesque drawings and brilliant watercolour palette. At Highcliffe, she immersed herself in creating stained glass windows to decorate the castle and village church.

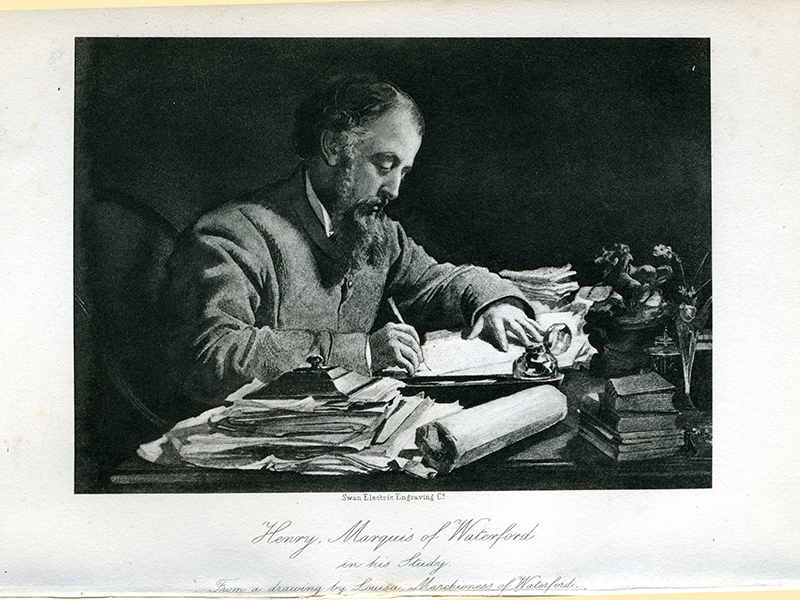

When her heart was captured, her choice made dramatic contrast with her own retiring nature. At the Eglinton Tournament, an extravaganza featuring chivalric jousting, baronial style banqueting, and a good deal of dressing up in Medieval apparel by haute société, Louisa became captivated by the dashing athleticism and horsemanship of Henry, Marquis of Waterford. The courtship proceeded gingerly; Elizabeth Stuart had marked reservations regarding the ‘wild Lord Waterford’ who had a rumbustious reputation as a prankster, daredevil and man about town. Louisa’s decision was quietly faithful, however, and she and Henry were married in 1842.

The social whirl of court life and the high society Season were now exchanged in Louisa’s life for the sleepy, rural surroundings of County Waterford in Ireland. A slower, more retrogressive nation than England, the position of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy was distant both from their cultural centres and from the culture and people who surrounded them. Louisa appears to have perceived no barriers. She rapidly threw herself into philanthropic activities to improve the quality of life of the people living on her husband’s estate.

The marriage itself was blissfully happy. Henry became a reformed character, devoted to his wife and the running of his vast Irish estate, Curraghmore. Louisa was immersed in her love for her husband, and turning the “holding” into a home. Regrettably the couple had no children, although they sought help over this, it was to no avail. Louisa threw herself into local work. She oversaw the building of two churches, for which she again designed and made stained glass windows. She established a school for local boys in the stables, and, with her husband, established a factory that produced woollen goods to give employment to local women. During the period of the Irish Famine, the Waterfords both moved decisively to alleviate suffering, setting up relief committees and soup kitchens, and importing grain for donation. Henry paid destitute farm labourers at the rate of a penny day to build a wall around the estate.

Many months of the year were passed in social solitude by the couple. Louisa’s life became more alone during the hunting season, when the couple removed to their hunting lodge at Rockwell. Louisa was by herself throughout the day. Replete in her self-reliance, she practised her art work at these times. Her style developed. Greater distinctness emerged, narrative and expressive atmosphere increased, and her paints took on the bright watery hues typically created by the playful Irish sunlight.

It was during these happy years that Louisa began to take lessons from John Ruskin to improve her art. Ruskin was at the height of his powers and the peak of his fame as a philosopher when the lessons began. As tutor, Ruskin was a task master, mordantly and persistently critical of Louisa’s failed efforts to take up his instructions to paint more accurately and with greater finish. Ruskin’s style of mentoring was stringent and proscriptive, quite divergent from the inspiration of the universal creation espoused in his works. Louisa’s watercolours became rigid and over ‘finished’, or as Charlotte put it, lacking her usual ‘spirited style’. Ultimately Ruskin’s involvement elevated Louisa’s work to a superior level, however, the immediate effects of his insistence on ‘finish’, precision and truthful representation were frequently unsuccessful. There can be little doubt that in the early days of their tutoring arrangements, Louisa needed a happy life in the background to sustain her against Ruskin’s criticism, which not infrequently descended into personal, class-based invective.

Then suddenly, blindly, devastatingly tragedy struck. Whilst out hunting, Henry was thrown from his horse and died instantly. The grief Louisa experienced shook her to the core of her being. Her sorrow was awe inspiring to those who witnessed it. In the depths of her despair, it was her unerring faith in God and the precepts of Christianity that sustained her. In his Will, Henry testified to his great love for Louisa by bequeathing to her his estate at Ford Castle in Northumberland for the rest of her lifetime.

In the months soon after her arrival at Ford, whilst still in deep mourning, at a time when few occupations interested her, Louisa began work on improving conditions for the people for whom she was now responsible as landlord. In 1860, she initiated the building of a village school, so truly did she embrace her scheme that she undertook to decorate the school with a deep frieze of life-size watercolour murals depicting the children of the Bible: ‘Lives of Good Children’. The project would take twenty-two years to complete.

Louisa’s murals reflected a revival of monumental painting and fresco across the British Isles at the time. The fashion was stimulated by the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster, following its destruction by fire in 1834. Ruskin’s works also played a role in awakening national interest in frescoes and murals. Almost inevitably, Louisa consulted him on her new grand scheme. Despite his own influence, Ruskin deplored the murals, blaming Louisa for investing effort in Bible children when so many living children were in need, and for creating new paintings when so much great art was falling into rack and ruin in Italy. When he visited Ford in 1863, he certainly did not refrain from criticising the paintings. With customary rationality, Louisa absorbed what was productive: ‘Ruskin’s visit was only a morning one…. He condemned very justly my frescoes, and has certainly spirited me up to do better’. Undoubtedly the calibre of the murals improved after this visit.

Other lions of the art world were of a different opinion from Ruskin. Both George Frederic Watts and Edward Burne-Jones urged Louisa to ‘paint one of her designs on a sufficient scale, and with a degree of completeness that may satisfy posterity that there lived in 1866 an artist as great as Venice knew’. Her murals fulfilled their wish. Today, although little known, the beautiful decoration of the school room in vibrant hues remains a chef d’oeuvre of the period. As a scheme, the mural sequence was unparalleled by any other woman artist of Louisa Waterford’s generation across Europe.

Apart from her illuminate murals, Louisa made Ford seem like a little piece of Italy in other ways. At about the same period, the writer Augustus Hare reported that ‘The whole place is unique. The fountain in the centre of the village is worthy of Perugia, with its tall red pillar and angel figure standing out against the sky. All the cottages have their own brilliant gardens of flowers, beautiful walks have been made to wander through the wooded dene below the castle, and miles of drive on Flodden, with its wooded hill and Marmion’s Well.’ The pillar, designed by Gilbert Scott, was a memorial to her husband, Henry. The immaculate condition of the cottages and village were part of an extensive programme for the improvement of the living conditions of the tenantry on the Ford estate.

Louisa Waterford was a committed philanthropist. She participated not only in the old style lady-of-the-manor delivery of charity to individuals, but also in a new style of philanthropy, organised on a larger scale with practical basis. Initially her attention was placed on rebuilding cottages and farmhouses at both Ford and, another village, Seaton Sluice. Many more thousands of pounds were spent on farm improvements to assist farm workers. She built a second school at Collingwood. Further projects of a community based nature included a Young Women’s Help Society, Sunday schools, which were an important source of education for labouring people, and the establishment of a group of lady parish workers at Seaton Sluice, whose wide range of activities were financed and accommodated through her support. The latter group, known as The Mission, was established in 1885 to assist the neglected colliery villages of the area. All these philanthropic activities substantially reduced Louisa’s own income from the Ford estate, however, as the village chaplain, Neville Hastings, wrote ‘money she regarded simply as a means of doing good, and her gifts were measured by the importance of their object’.

Louisa’s interest in the hard lives of rural workers manifested increasingly in her later drawings and watercolours. Titles such as The Bondagers, The Gleaners, Three Bondagers, Bondagers taking Potatoes out of a Heap, Bondagers, An Old Man Bearing a Sheaf of Corn, abound. Further works depict farm labour in combination with religious themes: A Time to Sow, Man Goeth Forth to his Labour till the Evening, and The Sower, filled with haunting power. There can be little doubt that Louisa’s extensive charity emanated from her deep religious faith and Christian humanitarianism.

As time progressed the companionship that art offered in Louisa’s life increased. She suffered further bereavements. In 1861, Charlotte died, followed by her mother in 1867. In the absence of close intimate ties, Louisa seems to have poured the essence of her humanity, her profuse love of life, and her fascination with the mystery of spirit into her art. Perhaps this accounts for the eclectic range of her subjects, taking in biblical stories, allegorical themes, ideas from literature, scenes from daily life, nature, and, of course, her copious and delightful studies of children and childhood innocence, whether in the drawing room, school room or at work on the land, in pictures such as Children Gathering Sticks, Boy Minding Crows Three Children Carrying Bundles of Birds.

In later years, her painting and drawing matured. Released from Ruskin’s critical gaze, the expressive ephemeral quality returned to her work, whilst at the same time the more defined style and greater ability to bring works to completion, achieved through working with him, remained present. Her works deepened in eloquence through the blending of structure with freedom of form, movement, and intensity of emotional atmosphere. This, combined with a deeper more gem like palette, produced some exquisite results. Louisa exhibited successfully at the Dudley, Grosvenor and Whitechapel galleries and assumed a semi-professional approach to her art, producing works for sale to raise money for charity.

After her death in 1891, posthumous exhibitions of her work were held at the Royal Academy and Carlton House Terrace to considerable acclaim. J. C. Horsley, R.A. commented, ‘Lady Waterford’s really resplendent genius is a revelation to all, and one is at a loss which to bow down to most, her lovely poetic thoughts, and impressive rendering of the holiest subjects, or her astonishing artistic gifts of colour and composition’.

After her death, Watts also spoke in glowing terms, ‘Our time has only produced some twenty real artists, and Lady Waterford was one of the greatest among them. In colouring she is a Tintoretto, and in the grace and ease with which she threw her figures on the canvas she equals the greatest masters. I am a child compared to her, though I have painted all my life’.

The vivid spirit of Louisa’s inspiration continues to be transmitted today through her beautiful murals in the windswept country of Northumberland and through her many smaller works held in collections about the British Isles.