Embroidering

A poem by Frances Richards (date unknown)

She embroiders heads; small children sitting

With spinning tops on blue velvet

A light-footed dancer, delicately darned on lace

With flowers, like a garden, as a background.

Does she think as she sews her silks and velvet,

That she is weaving a paradise of her own mind and eye?

Or do the never-ending movements of the needle

Revert her to a past unconscious state

Such as that of a mother rocking her child to sleep?

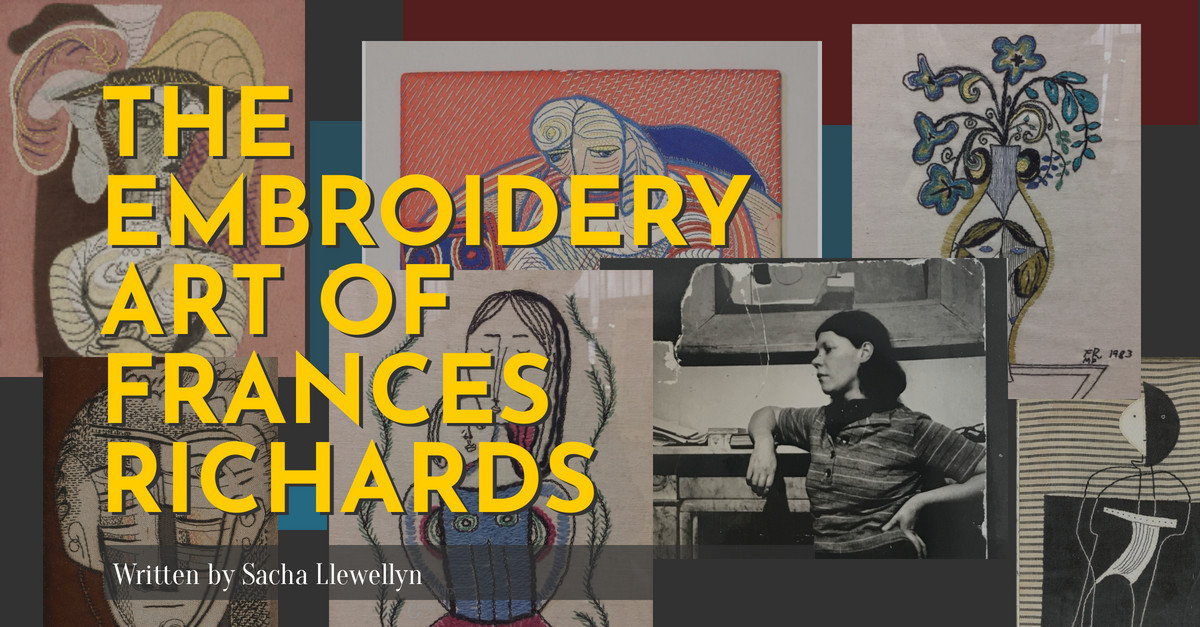

Frances Richards (1903 – 1985) worked as a painter, draughtswoman, fresco artist, potter, sculptor, teacher and poet. From the mid-1940s, she also reclaimed the traditional art of embroidery as a modernist project, creating distinctive toiles brodées through which she explored an imagery focused on the female condition.

Born in Stoke-on-Trent in 1903, the daughter of pottery artist John Clayton, Richards worked in ceramic design before moving to London to study at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in 1924, where she learnt to work in many media, including line engraving and lithography. Using these skills, she illustrated a number of private press books, including The Book of Revelation published by Faber and Faber in 1931. A particularly furtive time to study at the RCA, which was then under the tenure of William Rothenstein, Richards’ contemporaries included Enid Marx, Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and Ceri Richards, her future husband.

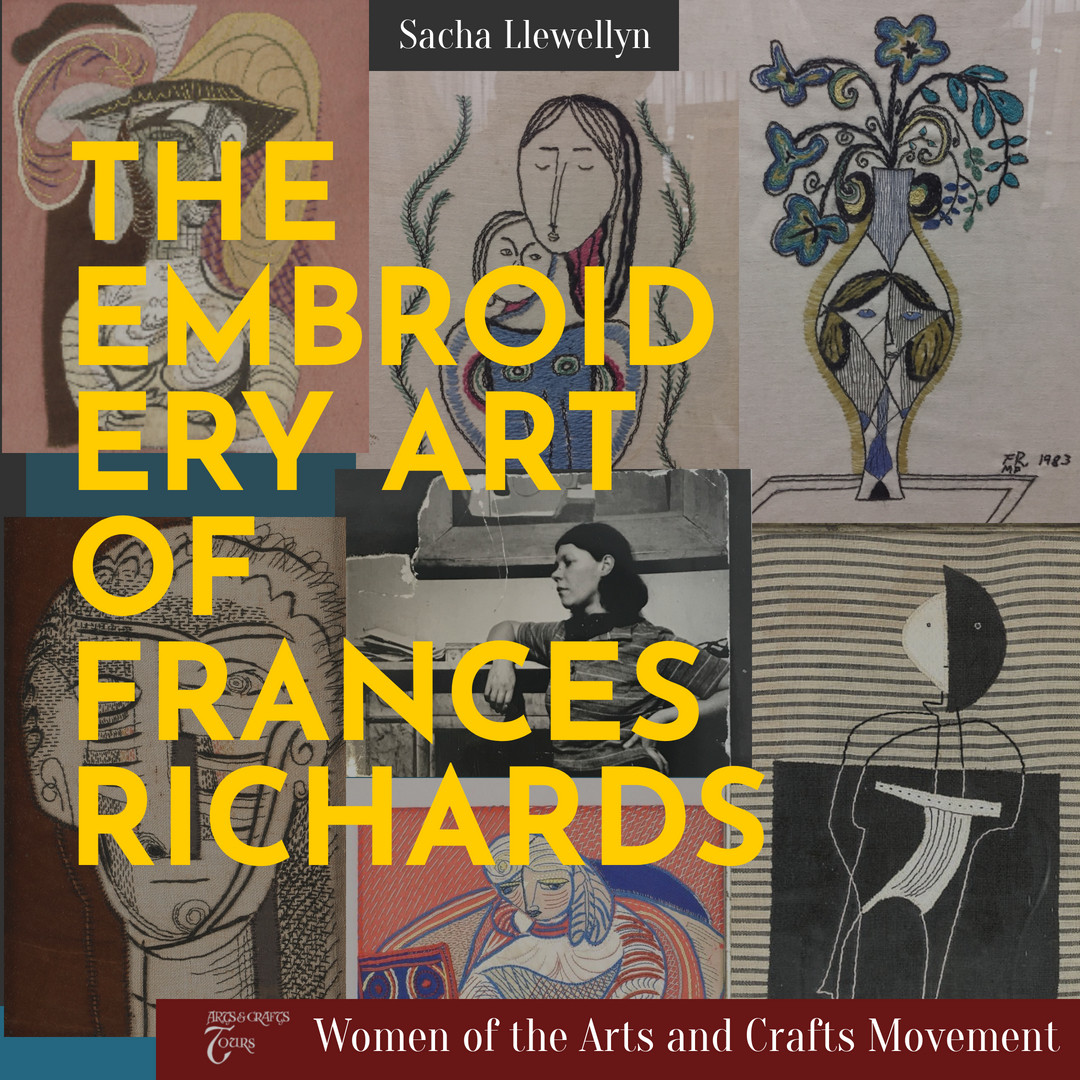

In the mid-1940s, when teaching at the Camberwell College of Art, the Principal, William Johnstone, a progressive artist and educationist, suggested Richards take up and teach embroidery. Over the course of a single weekend she taught herself enough techniques –chain stitch, running stitch and couched work – to create an original genre of needlework pictures which she would refine over the next three decades. Pared down to a simple, lyrical essence, Richards’ hallmark toiles brodées combined simple embroidered lines with pattern darning and textile collage elements worked on rectangles of white or off-white woolen or linen grounds. Unlike her husband Ceri, Frances Richards’ propensity to work on a small scale was in part a result of not having access to a studio – she worked on the kitchen table. An article in the Studio Magazine titled ‘Contemporary Needlework Pictures’ (1955) considered that Richards’ embroideries resembled ‘pages from a notebook set against a low-toned background bearing what appear to be pen drawings or engravings, but which on closer view prove to be lines of fine black stitching’.

Through the depiction of Picassoesque female figures and children, alone or in groups, Richards’ toiles brodées conjure up a distinctly female imaging of maternal love, fear of loss and feelings of solitude and vulnerability. Much of her subject matter articulates the sense of sadness and alienation that she felt during the Second World War, when she was separated from her family for long periods of time and became deeply affected by the plight of European refugees.

Through her embroidery pictures, Richards successfully contested the hegemonic distinction between the fine and applied arts, taking inspiration for content and structure from modernist sources. Not surprisingly, she did not exhibit her embroideries at Arts and Craft fairs or exhibitions, but had numerous sell-out shows at London’s Redfern Gallery. Even so, when The Times reviewed her exhibition of 1949, the toiles brodées were seen to possess ‘admirable tact and taste’ and were described as ‘pretty rather than fashionable’; the inherent assumption that the art of embroidery was a natural proof of femininity proved difficult for Richards to surmount. Although largely overlooked, partly as a result of being overshadowed by her more famous husband Ceri, Richards was recently the subject of an exhibition at the Glynn Vivian Gallery in Swansea (2019) and her work is held in various collections including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Contemporary Art Society for Wales. While Tate has a tempera painting and several lithographs by Richards in its collection, they have yet to acquire an embroidery picture.