In 1894, the Scottish architect Ninian Comper was presented with a glorious opportunity to design a crypt chapel for the church of St Mary Magdalene near Paddington. The parish church was established in the 1860s as a daughter church of the London Anglo-Catholic church par excellence designed by William Butterfield, All Saints Margaret Street. Both were loved by the poet and architectural writer John Betjeman, whose support for Comper included campaigning for a knighthood. In this period, the area surrounding Paddington station along the canal that stretches from Edgware Road and turns towards the wide expanses of west London was an area of serious socio-economic deprivation. High Anglican responses to urban poverty, inspired by the nineteenth-century Oxford Movement’s turn towards a stronger focus on the sacraments and the traditions of the Church prior to the Reformation, tended to result in sacred architecture embellished by bright stained glass windows, refulgent Christian iconography, and neo-medieval styles.

George Edmund Street was among the most significant Gothic Revival architects of his day, and his office was particularly renowned for supporting young designers like Philip Webb who went on to be leading lights in the Arts and Crafts movement. Street was responsible for St Mary Magdalene, and its recent restoration has brought Street’s 1860s vision to life again for diverse twenty-first century audiences. Some three decades after Street’s church began to rise along the banks of the canal, Comper was invited to produce his chapel for the parish’s first vicar.

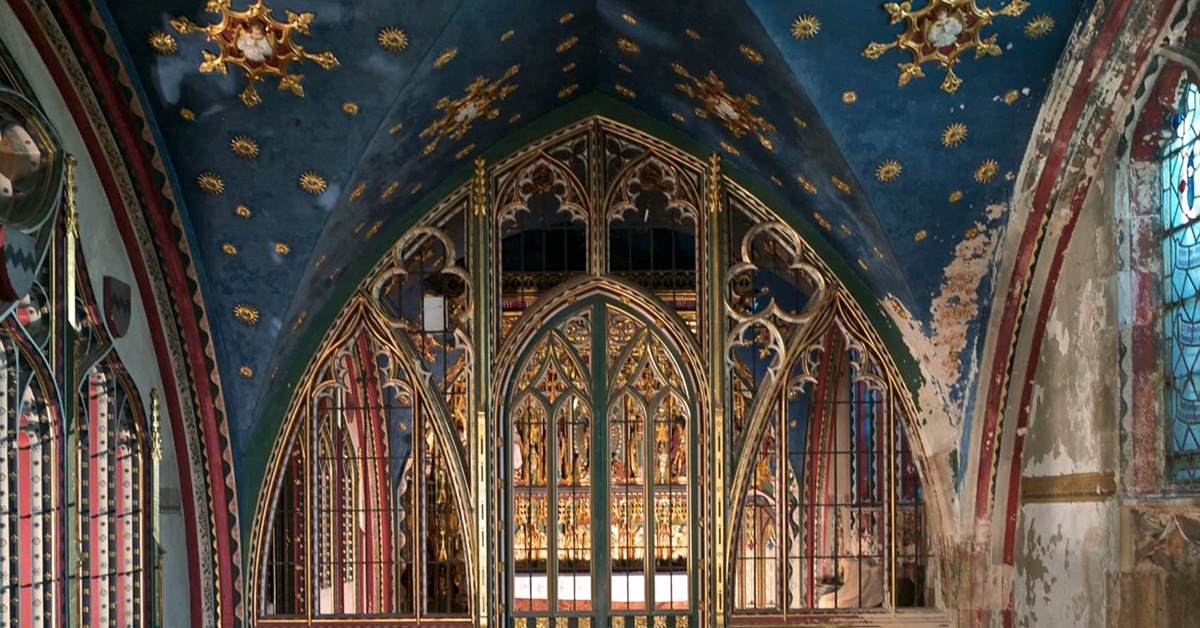

Entering the chapel is like stepping inside a fifteenth-century Northern Renaissance painting. The stained glass windows nearest the altar were inspired by Last Judgement scenes painted by Hans Memling and Rogier van der Weyden. The organ case features elegant decorative patterns framing a diptych of Mary Magdalene and Jesus in the garden on the morning of the Resurrection, when Mary recognises her Lord and he responds with his famous phrase, ‘noli me tangere’. The tenderness in these figures is timeless, transcending their late medieval style. The ceiling vaulting is aglow with gilded stars. Each one has a tiny convex mirror at its centre, and in candlelight they would have shone with the brilliance of any constellation.

The ceiling also features richly painted images of angels, watching from within their deep blue heavenly realm. The colour of the ceiling, which was restored in the late twentieth century, is no longer the rich dark blue Comper intended, though its cobalt tone doesn’t diminish the overall effect of Comper’s intricate subterranean space. Inspired by chantry chapels, the chapel also has a significant British inspiration in no less than the crypt chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary at Canterbury Cathedral. At Canterbury, the delicately skeletal tracery frames a sacred site at the very heart of the epicentre of Christianity in England.

Comper’s unique mixture of Netherlandish and British medieval and Renaissance references in this 1890s space was an early attempt for the young architect to express what he called ‘Unity by Exclusion’. The concept was to ensure that only the most purely refined aspects of Gothic art would be combined in something of a secret formula that produced designs which were as recognisably revivalist as they were freshly innovative. In this strategy, Comper followed his architectural mentor closely.

Comper was not trained in G. E. Street’s office, but by George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner. One of Comper’s first architectural epiphanies was Bodley’s design for St Michael and All Angels in Camden Town, built when Bodley really hit his stride as a Gothic Revival architect who turned towards late medieval English architecture for inspiration and counted Pre-Raphaelite artists and Arts and Crafts architects amongst his closest friends. Bodley honed his vocation in George Gilbert Scott’s office, but took a different direction in his pursuit of what he called ‘refinement’, aiming for elegance through a use of colour, pattern, and geometry that had more in common with the Aesthetic Movement and artists such as Edward Burne-Jones and D. G. Rossetti than with the blazing colours and assertive French-inspired forms of A. W. N. Pugin and his contemporaries in decades before.

At the Comper Chapel dedicated to the Holy Sepulchre, a close look at details provides delight and surprise, and even the best photographs are really no substitute for a visit in person. Plainsong from liturgies is painted around the interior walls, turning the chapel into an atmospheric choral experience of prayer even when there is no one there to sing or play.

The high altar is a gleaming feast of gold and blue, and the central panel provided a clandestine space to receive the sacrament, the consecrated wafer representing the Body of Christ, at a time when it was controversial to do so. Stepping into Comper’s fin-de-siecle chapel is an experience like no other, and its status as an unsung canalside jewel is unparalleled in British architectural history. Happily, it is also getting a new lease of life, as conservation experts are at work to ensure that the Comper’s vision shines through and that the public can enjoy it for generations to come.