A word of explanation: the ‘Scottish perspective’ is mine but, for some years, I have been fascinated by the fact that so many of Ruskin’s own perspectives were Scottish. This has been well put by his first biographer, William Gershom Collingwood (1854-1900), who was Ruskin’s secretary, confidant and constant companion from 1881-1900.

A scholar, archaeologist and artist-designer in his own right, he designed Ruskin’s monument in the churchyard at Coniston.

‘If origin, if early training, and habits of life, if tastes, and character, and associations, fix a man’s nationality, then John Ruskin is a Scotsman.’ W. G. Collingwood, The Life and Work of John Ruskin. London: Methuen, 1893

‘The combination of shrewd common sense and romantic sentiment; the oscillation between levity and dignity, from caustic jest to tender earnest; the restlessness, the fervour, the impetuosity, – all these are characteristics of a Scotsman of parts, and highly developed in Ruskin … The English world owes much to Scotland, in conduct of war, and in enterprise of commerce and industry; but still more in literature. And above the rest four names stand pre-eminent: Burns; Scott; Carlyle and Ruskin.’

Ruskin’s focus on art and architecture was vital for William Morris (1834-1896) and those directly influenced by them, including and especially the artist Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and the architect Philip Webb (1831-1915) and the next two generations of architects and artists.

For the artists, architects and craftspeople of the Arts & Crafts Movement there were two books above all by Ruskin which they simply had to read: the (1849) Seven Lamps of Architecture and the Stones of Venice (1851-3). Morris and Burne-Jones read them together at Oxford, as undergraduates.

The chapter on the ‘The Nature of Gothic’ in the Stones of Venice was especially influential. Towards the end of his life William Morris described it as being ‘one of the very few necessary and inevitable utterances of the century. To some of us when we first read it … it seemed to point out a new road on which the world should travel.’

So, what does it say in the ‘Nature of Gothic’ that is so important, even to us today? Short of reading the whole superbly-crafted chapter to you out loud – which I strongly recommend by the way – I will focus upon the following ideas:

It is essentially about change in society, change needed then, and change needed now, for humanity has by no means made as much progress as we ought to have done.

Probably following in Pugin’s footsteps, Ruskin argues that the social structure of the Middle Ages allowed the workmen freedom of individual expression. It is a big claim and there are many threads which it would be interesting to follow through. Some cathedrals, Strasbourg for example, or Freiburg, or York, or Lincoln, or Wells, have teams of craftsmen that have existed, sometimes with short breaks, from the Middle Ages until the present day.

‘We are always in these days endeavouring to separate the two; we want one man to be always thinking, and another to be always working, and we call one a gentleman, and the other an operative; whereas the workman ought often to be thinking, and the thinker often to be working, and both should be gentlemen, in the best sense.’

One of the most valuable teaching experiences of my life was being a member of the Wells Cathedral West Front Committee from 1974 to 1986. At the beginning it was all too obvious that the Cathedral Architect, a very distinguished man, was a ‘gentleman’ and a ‘thinker’, who seemed to treat the Master Mason and Clerk of the Works almost as a servant and addressed him by his surname: ‘Wheeler’.

At the end of twelve years, a time of great accomplishment in conserving the 400 sculptures on the West Front, they called one another ‘Bert’ and ‘Alban’, and had become firm friends. Each realised that he could not have achieved what he had achieved without the other. They had learned to appreciate and understand one another in the face of a daunting challenge to the integrity of the cathedral.

So far as design and execution is concerned, Ruskin enunciates what he calls ‘three broad and simple rules’:

- Never encourage the manufacture of any article not absolutely necessary, in the production of which Invention has no share.

- Never demand an exact finish for its own sake, but only for some practical or noble end.

- Never encourage imitation or copying of any kind, except for preserving record of great works.

Personally, I regard all such rules, even from Ruskin, with a certain degree of scepticism. A right decision depends on so many factors.

Out of those 400 sculptures – ‘one half of our noblest medieval art’, William Richard Lethaby – only one was replaced with a new copy. Crucial to its success was the fact that the sculptor, Simon Verity, spent one whole year working as a conservator on the West Front so that he could totally and deeply understand the visual language and ‘feeling’ of the medieval art.

We can also appreciate his new original work in the south-west portal of the cathedral of St John the Divine in New York.

During the Arts & Crafts Movement, roughly from 1860 to 1930, the conventional practice was generally against Ruskin’s precepts. William Collingwood’s monument to Ruskin is a case in point: he designed it, but someone else made it. Happily, we know who it was …

Most Arts & Crafts architects specified minutely the nature of the construction and the nature of the ornament which they wanted.

I would expect that, in executing ornament, many stone or wood carvers would often have to resolve aesthetic problems on the scaffolding. In other words, there was more freedom to carve creatively than meets the eye.

What does the term ‘Arts & Crafts’ apply to? My evolving contention is that it is meant to express the essential overall unity of creative activity in which the ‘seeing eye’ of the artist and the skills of the craftsperson are melded together, and neither is more important than the other.

Many Arts & Crafts architects could be considered to be also an artist or a craftsman, sometimes both, and in a little while I shall show you a specific example.

Ruskin had identified in the Stones of Venice that there had come to be a chasm between those people who could think and those who could make with their hands.

In Ruskin’s vision of the future this chasm would be healed: ‘in each several profession, no master should be too proud to do its hardest work. The painter should grind his own colours; the architect work in the mason’s yard with his men; the master-manufacturer be himself a more skilful operative than any man in his mills; and the distinction between one man and another be only in experience and skill, and the authority and wealth which these must naturally and justly obtain.’

In articulating Ruskin’s line of thought, and making it to some degree a reality, the way in which William Morris organised Morris & Company is significant and was also influential both on individuals or the numerous craft guilds which came into existence: he carried out a series of personal experiments in different crafts media – teaching himself to weave for example, and learning how to dye the cloths that were produced by the weaving; designing stained glass along with Edward Burne-Jones, Philip Webb, Ford Maddox Brown, John Everett Millais and others.

Much later, Philip Webb wrote a detailed description of the dilemma in a letter to Alfred Hoare Powell dated 19 December 1904: ‘In trying to combine art with the crafts, there seems to me only two ways of making it … pay: one is to make comparatively few articles of a costly kind, and do them all by skilful designers in a small way. You doubtless know that our one – more or less – successful craftsman (he means William Morris) considered that wallpapers were only of value because the mechanical carrying on of the manufacture, paid, and the money enabled him, William Morris, to learn other crafts from the root up – but stained glass was only so far a success that there was one rapid & skilled designer who could supply him with designs, ad lib, and Morris could keep the colour right – but it could never be right good craftsman’s glass, because there were no draughtsmen who could translate the beautiful pictures into effective painting for glass.’

‘The other way is to take, as you are doing, the manufacturer’s pots under the hide-bound conditions of a ‘great industry’, and make certain cheap articles pleasant and pretty, and commercially successful, by doing enormous quantities cheaply …’ John Aplin (editor), The Letters of Philip Webb, Volume IV, pp 126-127.

An experience which Ruskin and Morris enthusiastically shared was reading the novels of Sir Walter Scott. Scott inspired in Morris the enthusiasm for medieval history and literature which later emerged in his art works (for instance the painted decoration, furniture and stained glass for Red House).

Morris derived from both Scott and Ruskin his passionately-felt stand for the importance of the crafts and of art in the lives of people, potentially everyone.

That understanding is still with us and is a most important legacy of the Arts & Crafts Movement for us today. People are hungry for beauty and dignity in their lives.

How, otherwise, would so many craftspeople survive as small businesses of one or slightly larger teams working together? Within 15 minutes of my home I can think of two furniture-makers, a potter, a stained-glass artist, a saddler, and a number of people working creatively with textiles.

C. F. A. Voysey (1857 -1941) said of Morris in 1896: ‘It is he who has done for me what I might not have been able to do for myself, made it possible for me to live.’ Builder’s Journal and Architectural Record, 1896.

Early Arts & Crafts Work in Scotland: Philip Webb in Scotland – purchase of the Arisaig Estate by Francis Astley in 1848.

Morris & Co. in Scotland and its influence.

Robert Rowand Anderson (1834-1921), three years younger than Philip Webb, based in Edinburgh, is on the cusp of being an Arts & Crafts architect. He had trained with Sir George Gilbert Scott in London and so Ruskin and the SPAB regarded him with suspicion.

Anderson’s emphasis on ‘fitness for purpose’ and praise for ‘excellence of form, function and expression’: ‘Anderson was very close to being an Arts & Crafts architect, but his attitude to restoration and continuing admiration of George Gilbert Scott means that he cannot be regarded as such’ (Annette Carruthers, The Arts & Crafts Movement in Scotland, A History, Yale University Press, 2013, p. 36).

W. R. Lethaby (1857- 1931) in Scotland. Melsetter, Hoy, 1898-1900, for Thomas and Theodosia Middlemore.

Some cottages and farm buildings were retained as well as materials and a wing of the old laird’s house. It is common in Scotland for new work to incorporate old. It suggests an element of respect for the work of the past, an unwillingness to discard the labour of forebears, perhaps in recognition of the difficulty of working stone. Ours is a very ‘stony’ country, rich in geology – Ruskin’s passion – and good building stone.

Lethaby may also have been thinking of that passage in the Seven Lamps where Ruskin says that ‘There is a sanctity in a good man’s house which cannot be renewed in every tenement that rises on its ruins’.

Lethaby contended that the SPAB was able to be ‘a real school of practical building’.

1877 – foundation of the SPAB by Morris and Webb and with Ruskin’s specific backing.

1884 – foundation of the Art Workers’ Guild, founded by young architects who were explicitly inspired by both Ruskin and Morris, and who sought to work with craftspeople and artists on an equal basis. Vide Peter Burman (editor), Architecture 1900.

3rd Marquess of Bute (1847-1900) a trail-blazer: Cardiff Castle, Castell Goch and – in Scotland – rescue of former sacred buildings such as St Andrews Cathedral &c.

3rd Marquess of Bute deliberately chose to work with Scottish architects, designers and craftspeople. He was strongly in favour of Home Rule for Scotland, which was rare at that time, second half of the 19th century.

Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society founded in 1887 (same year 3rd Marquess bought the Falkland Estate).

Robert Rowand Anderson (1834-1921), the design and building of Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute.

Decoration and furnishing of Mount Stuart by Robert Weir Schultz (1860-1951) and Horatio Walter Lonsdale (1844-1919). Role of stained glass and textiles. Establishment of the Dovecot Weaving Workshop, still active today.

Robert Rowand Anderson and architecture in Edinburgh. National Portrait Gallery in Queen Street, Edinburgh. Queen Street had been specifically criticised by Ruskin in 1853 in a lecture at the Edinburgh Philosophical Institution.

Romantic restoration of Falkland Palace with much careful thought and expertise, a partnership between the 3rd Marquess and the architect John Kinross (1855-1931). Like Robert Weir Schultz he had been trained by Robert Rowand Anderson, but had a strong archaeological bent which made him an ideal collaborator with the 3rd Marquess.

House of Falkland, 1890s – remodelling of interiors by Robert Weir Schultz and Horatio Walter Lonsdale (stained glass, mural paintings, painted decoration).

Ruskin’s Scottish Legacy:

The National Trust (1895) and National Trust for Scotland (1931).

The teachings of Ruskin’s great Scottish disciple, Patrick Geddes (1854-1932), are widely known and appreciated in Scotland. It is no coincidence that so many of the Arts & Crafts figures were born in the 1850s and 1860. Many of them survived well into the 20th century.

Guild of St George – founded by John Ruskin in 1871 when he looked around him at the cultural and economic poverty of British society and declared: ‘For my own part, I will put up with this state of things, passively, not an hour longer.’ His personal motto was To-day – not to put off doing things until tomorrow. What are we as the Guild doing To-day?

- We declare an overall commitment to Ruskinian principles, especially social ones, and to an extent to Ruskin’s economic and architectural principles.

- We are an educational charity in UK law – we create forums for the discussion of Ruskinian ideas and practices in modern contexts, and have an active publishing programme. A strategic priority in 2023 is to establish local groups who will read and discuss Ruskin’s writings.

- Our charitable tri-partite commitment is to art, craft and the rural environment.

- The Ruskin Collection was gifted by Ruskin to the Guild of St George and consists of thousands of works of art, artefacts, illustrated books and minerals. Today it is cared for by Museums Sheffield, in partnership with the Guild. A highly successful collaboration between the Guild, Museums Sheffield, and the London Gallery called Two Temple Place created a stunning exhibition during 2019 – Ruskin’s bicentenary year – called John Ruskin and the Art of Seeing.

- Ruskin Land – Ruskin urged that some part of English land should be ‘Beautiful, Peaceful, Fruitful’ – sharing of skills, schools, university students, local people.

- Ruskin in Sheffield, a cultural programme of events and activities that took place from 2014 to 2019 inspired by John Ruskin’s ideas on making lives better.

This month we are publishing a handbook, based on that experience, called Paradise is Here – Building Community Around Things that Matter.

The author is Ruth Nutter, a dynamic and inspirational personality, who has been the Guild’s Producer for the Ruskin in Sheffield 2014-2019 programme. There was no aspect of that programme that she did not design and carry out, though attracting countless collaborators, so she speaks of what she personally and powerfully knows.

The book has been endorsed by Guildsman Dame Fiona Reynolds, former Director-General of the National Trust, in the following resounding words: ‘This book is nothing short of inspirational. John Ruskin wanted to do something remarkable for Sheffield, and the work described here is remarkable too: and steeped in his values. The wonderfully engaging range of activities energised curiosity, life and joy among communities across Sheffield, and provides a model for all people, everywhere. To coin the most common response from participants: this is just lovely!’

Dame Fiona Reynolds is currently the Master of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge, and the author of a superb book which is totally imbued with the spirit of John Ruskin: The Fight for Beauty. The fight for beauty – expressed through buildings, landscapes, and the objects or artefacts through which we live the daily intimacies of our lives – is one in which we all, like Ruskin, need to be engaged.

Rod Kelly’s teapot; beautiful lettering … Lincoln Cathedral furniture commission.

The whole point of Ruskin in Sheffield was to ‘make a difference’ to the local communities of Sheffield, according to four of Ruskin’s principal ideas:

- No wealth but life – fair and equal enjoyment of the world around us

- The Rural Economy – craftsmanship (the ability to make things with head, heart and hands), ethical livelihoods, and proper care (or management) of the land

- Not for Present Use Alone – create and conserve for future generations

- Go to Nature – as a primary source of beauty, inspiration, education and artistic practice

There is not enough time to go into detail about the 76 mainly free projects which involved 50 professional artists and volunteers and engaged 25,000 audiences and participants. The programme cost £193,000 – funded in part by the Guild of St George but with generous contributions from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Arts Council England and a range of local funders. However, here are just one or two stories.

One of Sheffield’s urban villages is especially connected with Ruskin because it was at Walkley that he established the first Ruskin Museum with the beginnings of the collection with which he gradually endowed the Guild. Here are comments about the programme from participating organisations, first from the Walkley Carnegie Library:

‘We originally flinched at the idea of spray paints in the library and hanging paintings and sculptures in and on a listed building – what in the USA you call a ‘Landmark’, wonderful designation, is for us a ‘listed building’: but people learn to be creative from each other (my italics) when facing difficult tasks.’

And from the Walkley Community Centre:

‘Our commitment to supporting our community, including other local groups and businesses has been strengthened … Our involvement in Ruskin in Sheffield highlighted the amazing number of talented artists and craftspeople locally. This is something we have incorporated into our plans for a proposed refurbishment of our building.’

One highly successful project was the creation of the Pop-Up Ruskin Museum in Walkley in 2015.

Another story is about a fine historic house, its park and walled garden, a Grade II listed building, called Meersbrook Hall, less than two miles south of Sheffield city centre.

The Friends of Meersbrook Hall re-discovered that the Hall had been the Ruskin Museum from 1890-1953, an astonishing example of how knowledge can be completely lost in just over half a century.

The first event in 2016 was to throw open the Hall’s doors to the public with an event called Celebrating Meersbrook Hall. Local artists displayed contemporary crafts, offered hands-on carving and mosaic-making, alongside guided tours to signal a new era of welcome creativity and possibility for the Hall.

There has been a gradually evolving collaboration with the Heeley Trust which has been working for over 20 years to improve local public spaces, secure key buildings and other local assets for the well-being of the people who live in Meersbrook.

The Guild of St George now has its office in Meersbrook Hall.

I can sum up the spirit of the whole enterprise of Ruskin in Sheffield with another telling quotation, this time from the Friends of Walkley Cemetery. As in many countries and cultures, historic cemeteries are a particular kind of cultural landscape, rich in historical and artistic content and in plants and animals which otherwise rarely survive in urban contexts:

‘The time of the Pop-Up Museum and other parts of the Ruskin in Walkley programme were, for me, a time of excitement and exhilaration … I have always believed that art and creativity are essential parts of my and our lives, and everything that Ruskin wrote and that Ruskin in Sheffield has stood for confirm that belief.’

A decade ago, who would have thought that Ruskin’s words and actions could still have such consequences in people’s lives? We are living through a truly excitement moment where everyone involved discovers though collaboration and creativity what Ruskin means for them.

I have been enthralled by reading this handbook during the time of preparing this lecture. It is on the very point of being published, and I cannot recommend it too highly! Please see the Guild of St George website for information. Better still, become a Companion!

Finally, Ruskin in Scotland – who knows? I have devised a programme for a Ruskin study tour subtitled A Ruskin Pilgrimage in Scotland.

I have consulted various colleagues and friends, including Professor James Spates and Dr Clive Wilmer, former Master of the Guild of St George. Now I am embarking on detailed discussions with two fellow Art Workers’ Guild brethren, deeply respected as effective cultural tour guides, Elaine Hirschl Ellis and Past Master Peyton Skipwith.

During 2020-22, because of Covid-19 restrictions, even travel around Scotland was somewhat restricted: but gradually I have been putting together a powerpoint presentation which to show all the special places to which we can go. They would be special anyway – they include Sir Walter Scott’s Abbotsford, the four ‘Border Abbeys’, Rosslyn Chapel, Dunblane Cathedral, Brig O’Turk, Perth properties associated with the Ruskin family, and so on – but the link with Ruskin, to both his personal life and his thinking life, make them incredibly special in a whole new dimension, artistic and spiritual.

Finally, I want to sum up what I believe Ruskin’s legacy to be for us today whether we are sitting in North America, Scotland, England, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Japan, or wherever (we have Guild of St George members or Companions in all those places and more):

- We are indebted to him for his radical critique of the negative effects of over-industrialisation on human beings and on our precious environment.

How galling it is than in so many countries – including our own wealthy ones – countless human beings still live in over-crowded insanitary conditions and in great poverty.

- Ruskin demonstrated to us how it is the selfish activities of human beings that pose a grave threat to the natural world.

The statistics about the melting of the polar ice-caps, about the overall and specific consequences of climate change, about the rate at which animal and plan species are dying out – all these and more are mind-boggling in their horror but still there are many human beings who cannot even accept that these changes are taking place. But it is almost two hundred years since Ruskin pointed it out!

- Ruskin argued that all governments have a duty and responsibility to care for and protect equally all members of society.

Put like that, it seems so right and so simply. Especially those who are vulnerable, in whatever way, need the care and protection of government and its agency. However, on both sides of the Atlantic we are caught in the toils of big business and are able to witness the profligacy and selfishness of extreme wealth.

- ‘There is no wealth but life’: has anyone anywhere ever expressed more pithily and more challengingly the desperately short time we all have – whatever our station in life – to do something to benefit other people and our communities?

We are challenged to resist the negative forces of capitalism and to prioritise – a very 20th/21st century term – our creativity, and not to neglect our spirituality. This phrase is effectively Ruskin’s rallying cry: but we must also never neglect the words which follow afterwards.

- It is astonishing what wide ‘outreach’ Ruskin’s ideas still have.

I have mentioned the far-flung Companionship of the Guild of St George already: but we can also remember some of ‘great minds’ who have picked up Ruskin’s torch and run with it including such as Leo Tolstoy, the Mahatma Gandhi and Patrick Geddes. Patrick Geddes was a Scottish disciple of John Ruskin who was inspired to become the first professional town planner; he was Professor of Botany at the University of Dundee and so, like Ruskin, he had a scientific understanding of the world. He was influential as a consultant town planner and educator in France and India as well as in the British Isles.

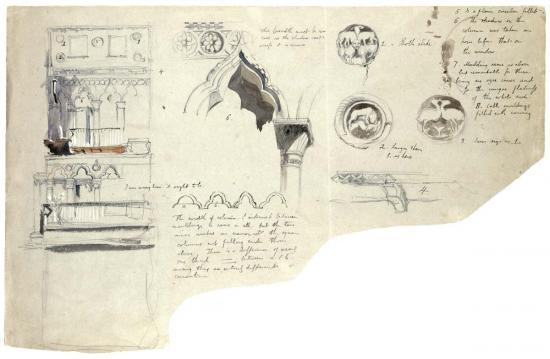

- He inspired Morris and others, including many of us today, by his ideas about historic preservation. As a member of the ICOMOS Committee on the Philosophy and Ethics of Conservation I am aware that the ‘Lamp of Memory’ and the ‘Nature of Gothic’ are still today the foundation stones for understanding and evolving a philosophy of conservation. At the University of York’s Centre for Conservation Studies, I used to give all my Masters students on their first day a copy of the ‘Lamp of Memory’ and a copy of the SPAB Manifesto in which Morris and Webb quote Ruskin’s actual words.

In The Storm Cloud of the 19th Century, Ruskin made us powerfully aware of the horrific dangers of pollution, whatever its source.

Mentioning the dangers of pollution reminds me of the essay on ‘Traffic’, in The Crown of Wild Olives and the following powerful utterance by Ruskin:

‘Change must come; but it is ours to determine whether change of growth or change of death … Better or worse shall come; and it is for you to choose which.’

I often reflect that you can learn a great deal about ‘great spirits’ like Ruskin from what their friends and contemporaries derived from them at the time. I was recently at the Watts Gallery, near Guildford in Surrey, established to celebrate and display many of the paintings and sculpture of the great Victorian artist George Frederic Watts.

It also celebrates the life and work of his remarkable second wife, Mary Seton Watts, who established a first-rate pottery there. She called him ‘Signor’ because of the powerful influence which several years in Italy had had on his life and his art.

The whole place is a little bit like what I imagine Roycroft to be, associated as it is with an Artists’ Village and with the Arts & Crafts house which was their come.

George and Mary were very friendly with the ceramicist William De Morgan and his wife Evelyn De Morgan, both writer and painter. All four regarded themselves as friends of Ruskin (Ruskin was one of nine friends who clubbed together to buy them a grand piano). They read his work and they understood it.

They were all four key members of the Arts & Crafts Movement.

Beneath one of Evelyn De Morgan’s paintings I read the following extract from the Diaries of Mary Seton Watts, 20 August 1893:

‘Mrs De Morgan is here, our only visitor. Signor (George Frederic Watts) lay in the niche and talked of the change that might be wrought for mankind, were he to realise that his present ideal is all for self, self-advancement, and chiefly by money getting for self, and instead was to fix eyes upon the grand universal idea of helping all to reach a happier and better state of things. A heaven might really dawn upon earth.’

We may note that Ruskin says ‘Change must come’; George Frederic Watts says that ‘change might come’.

Which is it to be, in our generation and time? Are we so very much opposed to a ‘heaven upon earth’ that our actions are going to continue to be ineffective against the mighty battalions of selfish wealth and power?

PETER BURMAN, revised 22 January 2023