George Bernard Shaw called her ‘the silentest woman I ever met’. And Henry James said she was ‘an apparition of fearful and wonderful intensity’. But these famous descriptions do Jane Morris a disservice. As a model for Gabriel Rossetti, she became Queen Guenevere, Pandora or Persephone. But should we accept that these images reflect the reality of Jane’s life and character? With the publication of her letters, edited by Jane Marsh and Frank L Sharp, we can recreate a fully rounded picture of the lives of both Jane and William Morris, their family and their close circle. As we read Jane’s words, we can reconsider the creativity of the women who pioneered the Arts and Crafts movement. Jane was an outstanding embroiderer, and ran the needlework department of Morris and Company for over a decade. She built a network of female friends and colleagues, and hosted poets, anarchists and artists at her homes in Kent, London and Oxfordshire. For the first time, we can see how she and William Morris worked together to develop a radical household. As he said, ‘the true secret of happiness lies in taking a genuine interest in all the details of daily life’.

We can see the gap between the myth and reality of Jane’s life, when we look at the letters she wrote soon after they moved into their new house on the river at Hammersmith in 1878. We can find her, leaning against a tree trunk, a book open in her lap. Jane was reading poetry, piecing together unfamiliar Italian phrases. From time to time she lifted her eyes to survey the shrubs and raspberry canes nearby, and ask herself: what else would grow well here? Later she wrote to William’s college friend, Cormell Price, telling him about her new home in Hammersmith. ‘It is a heavenly garden on a hot day’, she said, a delight to spend the morning ‘in an apple tree reading Tasso’.

Jane’s letter gives us an insight into the contradictory ways in which her life has been portrayed. From the moment she began modelling, her life was doubled – she became an artefact, as well as a flesh-and-blood woman. For her, the new garden was not simply a place of retreat. She wanted to concentrate on serious reading, stretching herself, while keeping out of the way of the builders. Jane also took time to consider what would need to be done to tidy, to reorder and restock the flower beds and orchard. And, as she told Crom Price, she did not want to be thought of as ‘a lazy fool’: ‘I have the new house on my hands’, she said, and that was why her brain felt ‘like a pudding’. She was busy planning, learning, supervising.

And yet, the idea of Jane sitting in a tree carries other associations – of idleness and distraction. One of Gabriel Rossetti’s most famous pictures of her, embowered in the branches of a sycamore, is called The Day Dream. The pose was developed from a drawing called Reverie, made at Kelmscott Manor. Both titles imply an absence. Jane is presented as passive, uninterested in her book, barely able to summon the energy to hold herself upright. In the sonnet written by Rossetti to accompany the picture, he dwells on her silence and dreaminess: ‘till now on her forgotten book / Drops the forgotten blossom from her hand’. But Gabriel himself knew the effort that Jane had put into creating this work of art.

Jane discussed the details of the commission with Gabriel. She suggested flowers that would be in season when the sycamore was budding. She offered to send snowdrops and anemones, and then, later in the year, honeysuckle cuttings. She provided the shimmering green dress made of tussore silk. We can almost feel it in Gabriel’s hands as he arranged the folds of drapery. He missed Jane’s presence. He told her how the dress ‘is replete with your memory, empty as it is now’. Jane was the essential part of the picture – her face, her body, her hands. But he needed her back again, to perfect his image of the woman, whose ‘Dreams even may spring till Autumn’.

In the finished picture, however, he effaced Jane’s work. Gabriel made her appear unresponsive, deathly pale. In truth, although her health was shaky and she was in pain – at times, she said, ‘I have fainting-fits still if I sit up for more than a few minutes’– she was always thinking practically about how to improve her situation. She was clearly trying to make Gabriel smile when she wrote about the ‘sea-weed baths at Ramsgate for people of a delicate constitution’. Jane told him, ‘one is made into a kind of pie with seaweed, when it is supposed that one absorbs vast quantities of Ozone’. And Gabriel liked nothing better than swapping stories with his friends about their ailments. Illness and money troubles dominated his correspondence in his later years. His paranoia made him an uneasy companion. His letters were often plaintive and upsetting. Jane had to tell him that she did not want to receive any more ‘Jeremiads’, and he apologised: he had been ‘subject to depression’.

Our impression of Jane has so often been shaped by the words and images created by Gabriel. However, in her correspondence with friends like Crom Price, we hear how Jane sounds more relaxed, sociable, as a busy wife and mother. In 1878, her daughter May turned 16, and she wanted to enjoy the fun of being young in London. Jane took her to garden parties, and to art galleries and concerts. May was also accepted as a student at the Government School of Design in South Kensington. There she would have a vocational training in the decorative arts – textiles and ceramics, jewellery, wallpaper and book illustration – as well as access to the vast collections of the South Kensington Museum (later called the V&A). May had grown up surrounded by people creating things for homes and churches. Now she was preparing to earn her living as a designer and maker. May’s decision to follow in her parents’ footsteps was bold but not unexpected. Still, it came at a particularly hectic moment, just when the Morrises were moving into their new house in Hammersmith. Jane wrote, in comic despair, to Crom Price, how ‘everything is topsy-turvy; no one can find anything, not even their temper’.

Jane knew that taking on the new house was a significant financial commitment. So she joked with Crom that the family ‘have all begun to think of what we could turn our hands to, in case of absolute failure in the Art line’. She told him, William ‘suggests shoemaking for the men, and plain sewing for the women,’ but Jane said she would ‘refuse, I won’t try to be respectable’. If they ended up in the workhouse, she threatened to ‘tear up my clothes all day’. She wondered if her next letter would be ‘dated from Hammersmith Union’.

It is a strange image – Jane and William and their girls reduced to nothing. Fear of destitution had hung over Jane’s childhood, with her family shifting from one poor lodging to the next. She had grown up in the back streets of Oxford, and now she was moving to a house, in William’s words, in the prettiest situation in London. Her comments to Crom Price are a reminder that Jane had not played by the rules as a young woman, when she became a model and married William. Her close relationship with Gabriel Rossetti also showed she was willing to sidestep convention. All too often, William has been portrayed as the rebellious one in their partnership. But in this letter, we hear Jane’s own defiant voice. This was the spirited side of her character, the woman who ‘roared with laughing’. She was happy to sit in a tree with a book of poetry, not from idleness, but from a desire to ‘keep up my old habit of reading every scrap that comes in my way’. Jane was open-minded, eager for knowledge, amusing. And willing to take on the challenges of a big house in need of renovation, while her husband ploughed on with his new projects – writing, weaving and designing.

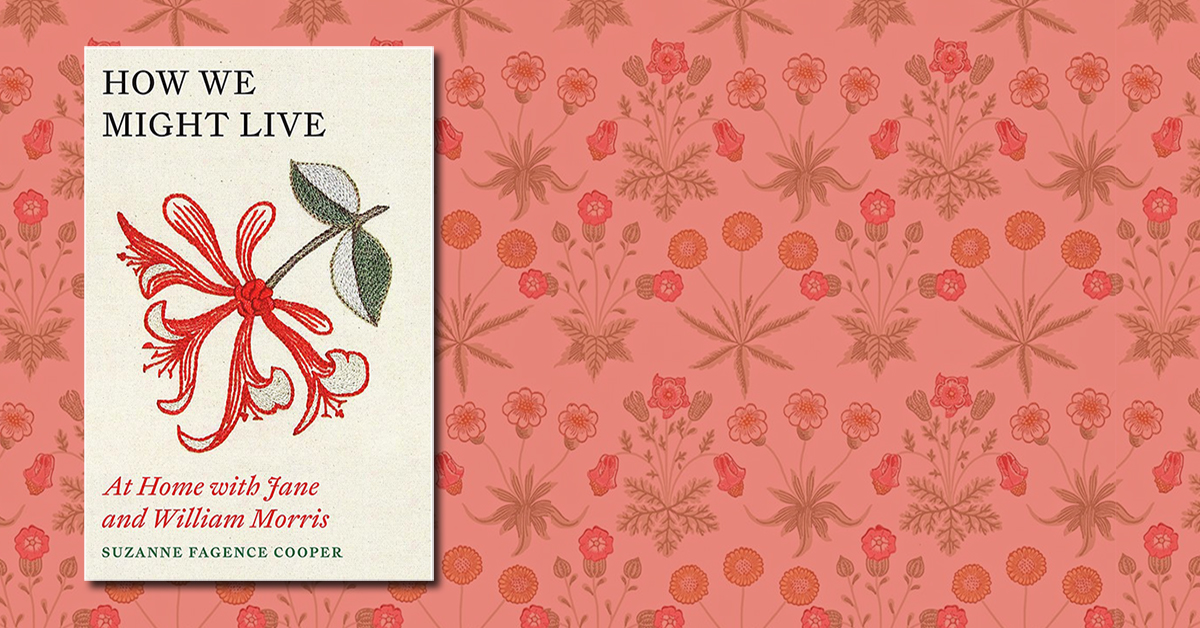

In this new biography, ‘How We Might Live: At Home with Jane and William Morris’, we travel with Jane to Italy and Egypt. We see how William’s journeys to Iceland helped him to reimagine his life and work of William Morris. And above all, we discover how they created a radical partnership in art and life.

The book is available in hardback at How We Might Live: 9781529409482: Amazon.com: Books, and on Kindle and audiobook via How We Might Live: At Home with Jane and William Morris: Amazon.co.uk: Fagence Cooper, Suzanne: 9781529409482: Books