Lincoln Cathedral: “the most precious piece of architecture in the British Isles”

Arts and Crafts Tours will be visiting Lincoln Cathedral this October. In anticipation of this visit, Jane Bingham reflects on how the cathedral has inspired some leading figures in the Arts and Crafts movement.

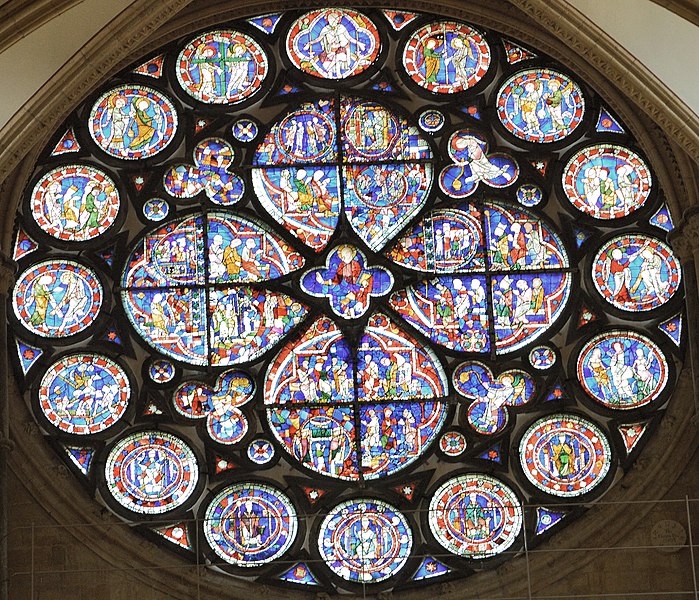

In a game of ‘Best British cathedrals’, Lincoln would surely come up trumps. Its commanding position on top of Castle Hill is almost as spectacular as Durham’s riverside perch. Its soaring triple towers can equal those at Canterbury and York, and its mighty west front presents a worthy rival to Exeter and Wells. And Lincoln’s interior spaces are dazzling too. Slim Early English columns support an intricate roof. Delicate stone carvings represent the best of the Decorated style, and twin rose windows provide the perfect framework for the cathedral’s stunning early medieval glass.

For the critic John Ruskin, there was simply no contest. With characteristic confidence, he proclaimed, “The cathedral of Lincoln is out and out the most precious piece of architecture in the British Isles and roughly speaking worth any two other cathedrals we have.” And William Morris agreed. Praising Lincoln cathedral as ‘‘a sort of miracle of art”, he especially admired its “careful delicacy of beauty” Less dogmatic in his judgments than Ruskin (when asked to name his favourite cathedral, Morris replied “Whichever one I happen to be in.”), he nevertheless made Lincoln a personal yardstick. In the words of his biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, “No other English minster he saw ever came close to it.” It’s possible to see the influence of Lincoln’s leafy carvings on Morris’s designs, while his stories and poems often feature a hilltop cathedral, just like Lincoln, towering over the surrounding land.

Morris’s circle of friends liked to play their own cathedral game. Prompted by Sydney Cockerell, Morris’s secretary, they decided that Ford Maddox Brown was Peterborough, Philip Webb was Durham, Edward Burne-Jones was Wells, and William Morris was Lincoln. Morris must have been delighted by their choice, which feels entirely right to me. Of all the English cathedrals, Lincoln – like Morris – is arguably the boldest, the most eccentric, and the most accident-prone.

Lincoln Cathedral had a shaky start. The original Norman structure was barely completed before an earthquake hit in 1185, leaving only a fragment of the west front, and over the next two centuries, the nave, choir, and transepts all had to be rebuilt. When its central tower collapsed in 1237, a spire was added to the new tower, but when that spire fell in 1549 it was wisely not replaced.

Despite its early troubles, the cathedral presents a solid face to the world – and it also boasts some very eccentric features. The meandering patterns on the ceiling of Saint Hugh’s choir have earned it the title of the ‘crazy vault’. The screen at the end of the nave is entirely smothered by carvings, and the cathedral’s bold west front combines two oddly contrasting styles, with airy gothic arches framing a massive Romanesque heart. Some surviving carvings around the original doorway offer a tempting glimpse of the magnificent scheme that once covered the Norman cathedral’s west front. A row of beak-headed monsters frames the doorway while a frieze of Bible scenes includes Adam and Eve biting on apples, Noah building the ark, and souls descending to hell – all of them carved with naivety and charm.

Lincoln’s oddity must have held a special appeal for Ruskin, who admired the medieval style as a direct expression of the craftsman’s art. In his seminal work, The Nature of Gothic, Ruskin offers advice to anyone approaching a medieval cathedral – and his words are especially appropriate at Lincoln.

“Go forth to gaze upon the old cathedral front, where you have smiled so often at the ignorance of the old sculptors: examine once more those ugly goblins, and formless monsters, and stern statues, anatomiless and rigid; but do not mock at them for they are signs of the life and liberty of every workman who struck the stone.”

One artist perfectly at home with oddity was Duncan Grant, the leading artistic figure of the Bloomsbury Group, whose murals of Christ the Good Shepherd among the Lincolnshire wool merchants decorate the Blaise chapel in Lincoln Cathedral. The intriguing story of how the murals came to be commissioned in the 1950s, and the mixed reception they encountered is told in Simon Chesters Thompson’s article, A Lincoln Surprise – Bloomsbury at the Cathedral. In particular, there were strong reactions to the evident physicality of Grant’s male figures. In fact, there is a robust tradition of bawdy art in medieval churches and cathedrals. Take a careful look around Lincoln Cathedral and you’ll discover a gallery of grotesques, including the famous Lincoln Imp squatting high in the nave, and an ominous green man, a pagan symbol of fertility, hiding under a choir stall.

Cathedrals are inspiring, but they can also be surprising, amusing, and even shocking – and that’s what makes exploring them so rewarding.