The role of women in the Staffordshire pottery industry contrasted greatly with the female artists at Henry Doulton’s art department in London. Doulton was concerned about working conditions in Burslem when he expanded his business there in 1877. As he said, “In Staffordshire, I have seen women and young girls employed in the most coarse and degrading labour such as turning the wheels, wedging the clay etc.”

Traditionally, women worked as menial assistants to their husbands and fathers, doing strenuous work for 8 to 10 hours a day. Only boys could be apprenticed to learn the trade. As the factory system developed, women worked on semi-skilled repetitive tasks, such as slip-casting, and transfer printing to decorate tableware and toilet ware. Girls as young as nine years old worked with toxic materials in abominable conditions, vulnerable to lung disease, known as “potter’s rot”, and lead poisoning, which caused abortions.

At the beginning of the 20th century, women represented nearly half the workforce in the Stoke-on-Trent potteries. However, men tenaciously guarded their positions as painters and gilders and even prevented women from using gold and armrests so that they could not do the fine, lucrative work. In the wider world, women were agitating for their rights and were lampooned by cartoonists. The Doulton Lambeth pottery produced inkwells of an ugly woman mocking “Votes for Women” in 1908. Finally, after their heroic efforts in World War One, women’s suffrage succeeded in 1918 with votes for women of 30 or over. In 1928, the age limit was reduced to 21 equalizing voting rights between men and women.

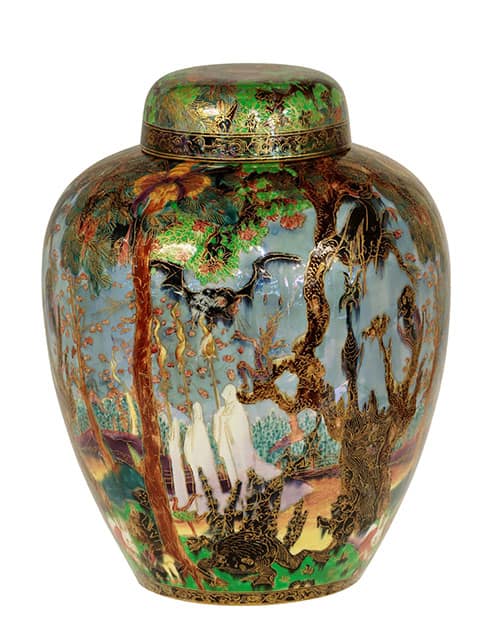

During this traumatic era, Wedgwood’s Fairyland Lustre ware was very successful in the luxury market. Wealthy customers could escape into a fantasy world of gilded forests and gardens populated with pixies and elves, created by Miss Daisy Makeig-Jones. Daisy’s ambition to be a designer took her from Torquay art school to the Potteries, where family friends secured her a job at Wedgwood in 1911. However, first she had to learn to be a paintress on the shop floor, at the same time as Louise and Alfred Powell were reviving free-hand painting at the factory. Wedgwood had perfected a new form of liquid lustre decoration, and this combined with Daisy’s dreams for the launch of Fairyland Lustre in 1915. Generally, Daisy preferred the darker denizens of fairyland and there are few fairies in diaphanous dresses with butterfly wings. Her designs were printed, hand-painted, gilded and fired six times to achieve the iridescent rainbow colors. Fairyland vases, plates and bowls continued to dazzle during the roaring twenties, but sales waned after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the Great Depression. Daisy was fired by Wedgwood but refused to leave the factory until after a huge row when she arranged for all her work to be smashed in her studio.

One of the greatest success stories of the Depression era was Clarice Cliff. She was born into a large family in Stoke-on-Trent in 1899 and started work as a painter at a local pottery at the age of 13. At the same time, she attended evening classes at Tunstall School of Art before joining the Wilkinson factory as a lithographer on her 17th birthday. Clarice soon impressed the management and became romantically involved with the owner Colley Shorter, an older married man. He arranged for Clarice to attend sculpture classes at the Royal College of Art in London where she was introduced to the latest design trends in Europe.

Clarice returned to her own studio at Wilkinson’s and her Bizarre Ware was launched in 1927. These exuberant designs were hand-painted in vivid colors by a few girls and immediately captured the attention of the British public, anxious to overcome the drab, greyness of their post-war surroundings. Within a year, Wilkinson’s entire Newport pottery was given over to Bizarre ware with hundreds of girls painting the abstract Cubist patterns on radical angular shapes. Her decorating girls gave in-store demonstrations wearing artist’s smocks and photo opportunities showed Clarice taking tea with celebrities of the day. The publicity that Clarice received in the national press was unprecedented. The public was fascinated by this new career woman of the 1930s, one of the first female art directors in the pottery industry and one of the first to brand her work.