Since 1973 Jenny and I lived with our two children at the northern tip of the north western island of the Outer Hebrides. While there we lived in and gradually restored a Thomas Telford manse, or vicarage, built in 1829, half-way between the village of Cross and the sea.

We had goats, cows and chickens and grew on our land oats for the cattle and vegetables for ourselves, and the excess we sold in Stornoway, the local capital of the islands, which was almost 30 miles away.

We cut peat from the moor for our fuel and in time our children went to the local school in the village, where they were taught half in English and half in Gaelic.

We had no knowledge at all of Mackintosh or Macdonald or of the cultural history that they were part of.

We earned money through Jenny designing and making beautiful multi coloured coats and other clothes from the local wool, which I twisted from the yarn used to hand-weave Harris Tweed. In time this became so successful that we were employing a dozen local ladies and exporting everything we made to London, Canada and Germany.

Fortunately, when Jenny decided that she hadn’t come to live on a remote island to run a mega international business, a friend of ours, a local girl, had just started a knitwear business, and so was able to employ all our ladies.

At that point I teamed-up with a local newspaper run by friends of ours and started bringing up to the island young unknown bands from the mainland to play in village halls. That also proved immensely successful, as there was nothing else in the way of entertainment for young people on the island.

However, we never forgot we were first and foremost artists, who had first met in 1967 and set up a studio together in St Ives, that mecca for artists near Land’s End in Cornwall.

So, in 1985 when we saw an advert for designs for the upcoming Garden Festival to be held in Glasgow, we immediately came up with several ideas and sent them off to the organisers. They responded and we went down there to have a meeting. Sadly, many of our ideas were then used without any credit coming to ourselves, nor were we offered any of the work to carry them forward into fruition. I guess we had straw behind our ears and were somewhat naïve.

No matter, we realised that the artistic skills we had built-up would go well in this city and so we moved there and rented a beautiful flat in a wonderful 1850’s crescent, designed by Alexander Kirkland, who went on to become chief engineer of Chicago. We made our studio in a lovely large sunny room with an open aspect. Soon commissions started to roll in.

However, it wasn’t until we entered and won the Scotland-wide open art competition to be artists for a new up-market shopping centre in the most prestigious street in the city centre, that we really started to make a name for ourselves, and began to get well paid for what we did. Certainly, winning that commission completely changed our lives, and it was then that we became aware of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

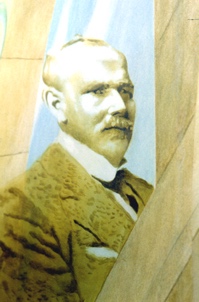

The reason was that as part of our winning entry we came up with the idea of painting life-size anamorphic trompe l’oeil portraits of famous people of Glasgow’s past, and one of them was Mackintosh. We painted them in an illusionistic setting of arches on the walls of the escalator from the street up to the food court on the first floor.

The impression you got as you ascended the escalator was the portraits being recognisable as you approached them, but unrecognisable and elongated as you passed them. This was in the same manner as the skull, hidden within the carpet, in Holbein’s portrait of The Ambassadors.

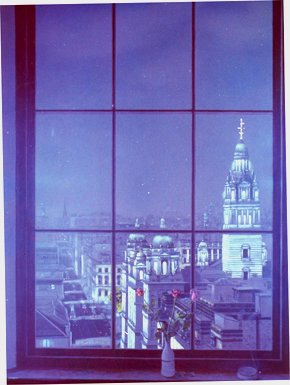

In addition we created two large illusionistic windows in the food court which gave a view over the city centre and which, with the aid of lighting changed to a night time view in the evening with all the city windows lit and street lights and car headlights shining.

This all proved so popular that we were asked to do a number of additional installations, including the calibration of a Foucault pendulum clock and a sculpture for the exterior of the street frontage. We also were invited to join the architects design team which led to commissions around the country.

When the City won the prestigious honour of becoming the first European City of Culture for 1990, there was a city-wide competition open to all architects, designers and artists to design Festive Lights for the most prestigious place in the city, George Square in front of the city Chambers.

After much debate we were chosen and succeed in transforming the whole space.

This too proved to be a life changing commission, which led onto us designing festive/Christmas lighting in various towns and cities in the UK.

However, more importantly in many ways, this led onto our introduction to the life and work of Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh. How this happened is as follows.

All year from the 28th of January 1989 we concentrated on designing these city lights, and it was due to this project we found ourselves working with the structural engineer Graham Roxburgh, who was appointed by the council to oversee and generally make sure that our vision was feasible by building the structures to display our lights.

All features were to be three-dimensional armature sculptures. Highest of all, as though floating above the city, were ten-foot-high angels atop 60-foot poles, and painted in blacklight paints and illuminated by ultraviolet flood lights.

Below them, suspended on catenary wires, were huge bells, interlocked in sets of three, which appeared to ring through the trickery of sequenced lights. And suspended between the bells were large holly leaves and Stars of David, which seemed to pulsate.

This was a major undertaking, not just for us, but also for all the metalworkers and technicians involved, and when, in late autumn, we finally handed into Graham our last scale maquette, which was of a hypocanthus, it was a major relief.

I remember he looked at what we had brought approvingly and then said “I’ve got a little project which I’d love you to help me with. It won’t take long. I’ll be in touch. I’ve really enjoyed working with you all year and I think you’d be perfect for what I have in mind.”

About a week later he rang and explained that what he had in mind was us joining his design team to work on a house that Mackintosh had designed but which was never built. We listened to what he had to say. Jenny shook her head, and I said he would be better contacting people at the art school or Kelvingrove. We didn’t know anything about Mackintosh, except for the fact we’d painted a portrait of him on the escalator walls. So, sorry but we’re not the people he needed. We put the phone down.

A week later he rang again. He said he’d spoken to people at the art school, Kelvingrove Museum and the Hunterian, but they were academics. They didn’t actually make anything. They knew all about Mackintosh but couldn’t help with what he had in mind, hands-on. Once again we said we couldn’t help.

A few days later he rang again, and candidly reminded us of his help with the Christmas Lights, and that we owed him, to which I had to agree.

Right, he said, the least you can do is come and have a look at what I’m doing and what I’ve done so far. I agreed, and went to have a look.

When I got to Craigie Hall, which was his office at the time and which he’d bought and restored, he started off by saying that Mackintosh, when he was a young apprentice architect, had worked on the house, and showed me various door details he’d designed, the extremely impressive organ casing and some of the paneling in the dining room.

He said he was very proud of the restoration he’d done to the paneling and he said I bet you can’t tell which are original and which are the new ones. Enough to say that I immediately pointed out the new ones, to which he was rather mortified. I went on to explain that as we’d done a great deal of trompe l’oeil work in London, it was easy for me to spot the difference.

He explained that what he was doing was building The Art Lovers House which had been designed in 1901 by Mackintosh and his wife working together, as the brief for the competition in Vienna they were entering, stipulated that entries were to be by an architect working in collaboration with an artist. Obviously, this was perfect for the two of them, as Margaret Macdonald was an artist in her own right, and they’d already successfully worked together on various projects. However, the house was never built, as WWI put a stop to everything.

He then took me through to another large room and showed me a whole table of samples of various kinds, including a very small gesso panel. He asked what I thought of the panel, and as it was falling to pieces with bits coming off it, I said I didn’t think much of it.

Right he said. It was done as a sample especially for me by a lady who lives and works in Italy, and who describes herself as a gesso specialist. Do you think you could do better than that? I said I know we could do better.

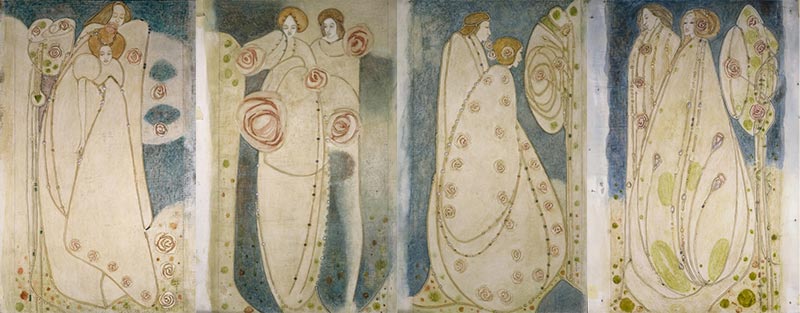

I thought so was his reply. He then went on to say that he had all kinds of things he’d like us to help him with, like design detailing artworks from Mackintosh’s original perspective drawings. He went on to say that originally, Margaret Macdonald would have done the gesso panels and that’d we’d need to work in the way she did.

I then went back home and explained to Jenny what the situation was. Naturally, she was very reluctant, but I finally managed to convince her that this was really interesting, plus we’d be paid. This was a deciding factor as we hadn’t received much from the council for our whole year’s work on George Square.

I seem to remember we started off considering the hangings beside the windows in the Music Room. These it turned out were very similar, to the hanging they’d designed and used as part of their room display in the Turin Exhibition of Decorative Arts in 1902. We reckoned these should be screen printed like the originals, but would be best if they were embroidered, as this would suit the affluence of this mythical patron of the arts, who was having the house built for him.

We then went on to consider the finials on the roof, and for these Grahame was insistent that they should be made with metal of exactly the same dimensions as the finials on the art school roof. He even asked that I measure the bolts which hold the design together.

This necessitated me climbing up to the East tower of the school, and a janitor holding a long ladder as I climbed to the top of a long pole to do all the measurements. There’s even a photograph of me up there to prove the lengths that we had to go to in order that every detail was correct. From this we made a scale drawing which was then followed by a metalworker.

Finally, we came to the gesso panels, for which he’d received funding for four of them from a firm of solicitors in Glasgow.

However, not knowing anything about Margaret Macdonald, nor anything about how she would have created the panels using gesso, we said we could only do this work if we were paid for a period of at least two months, to find out everything we could about Macdonald, her life, her likes and dislikes, the kind of paintings she admired, the kind of books she read, the music she listened to, and so on.

As part of this we would need to discover everything we could about gesso and working with it in the way she did. Very reluctantly he agreed to this, and so we set about discovering the life and work of Margaret Macdonald, and how she learnt about and then worked with gesso.

First we searched for and researched all the gesso panels that she’d done.